In black and white: Jenn Libby

Today photography is more accessible than ever. Almost every functioning member of society is carrying a phone in their pocket that boasts camera quality that rivals that of Nikon, Canon, or Kodak. Gone are the days of sifting through photo albums to see the finite ten to twenty baby pictures that have been archived, replaced with ten to twenty almost identical shots of a candid moment stored in the cloud along with 758 other pictures of a baby under eighteen months. In an age where everyone is taking pictures, how does one bring back the ephemera of photography?

“It’s like, why are people doing analog film photography? It’s messy, it’s stinky, you have to learn about all these chemicals. It’s harder when you have digital right in your back pocket. You have a good camera right in your back pocket.”

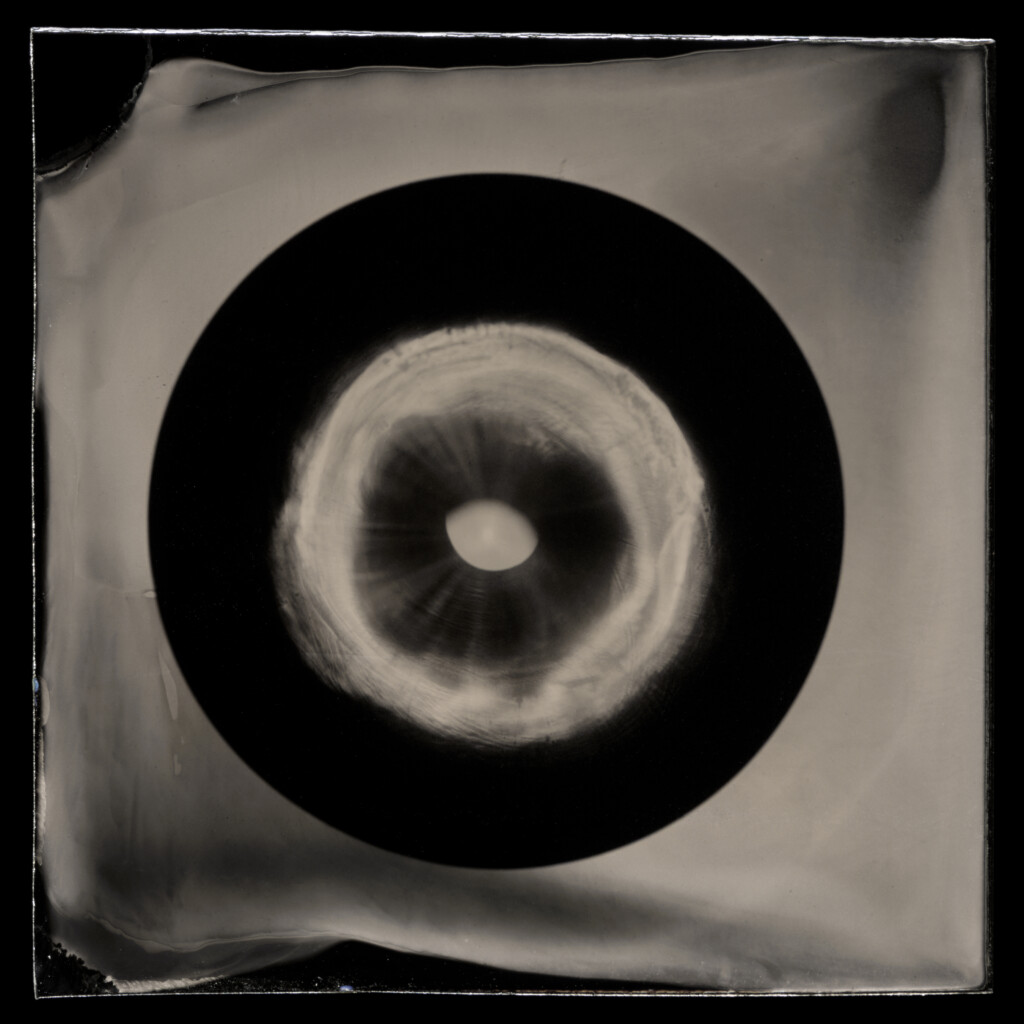

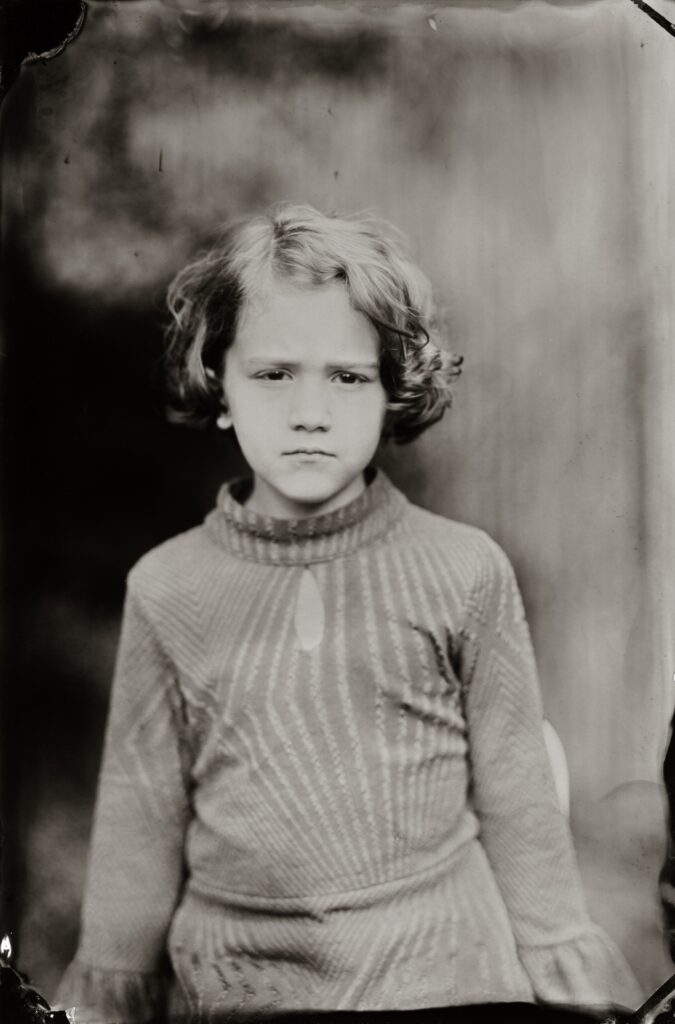

Jenn Libby and her portraiture business Genesee Libby Studio are well known in the Rochester artist community and analog photo scene for her wet-plate photography. An art that dates back to the nineteenth century, wet-plate collodion photography creates an image on a surface through a process of chemical application, exposure, and development within the span of about fifteen minutes, all of which require the utilization of a darkroom. To most people this style of photography reads as something straight out of the Civil War. The images are always black and white and are both hauntingly detailed but also unnervingly different from the analog photography we see today.

“Wet-plate translates people differently. It’s sensitive to the blue end of the spectrum. So blue eyes look white. It just gives you a different perspective, just like black and white does in comparison to color. I was like, wow, I really like portraits in this,” Libby says from her photography studio behind her home in the North Winton Village neighborhood.

Her studio is densely packed with curiosities I’m dying to touch. Two huge cameras that look like they’d be worth a fortune on Antiques Roadshow take up a large amount of real estate, although she assures me that they are not from the 1850s but instead Kodak cameras from the 1920s. There is a cabinet full of dried insect specimens, an image on black glass suspended in liquid from Libby’s graduate thesis, a closet full of costume props for potential portrait clients, and a box of photographs she picked up from an estate sale years ago that she is trying to restore to their former glory.

Her walls are covered in pictures, both modern portraits she has taken and a collection of vintage wet-plate ambrotypes and tintypes from the golden age of the process. In Libby’s studio you can see the past, present, and future all within your field of vision, including her darkroom full of all the chemicals that make the photo come to life.

I’m struck while Libby explains her process of how precarious getting the “perfect” shot really is. “When you make a negative in a camera, it’s reversed. But then you make your print and you re-reverse it back to normal. So, when I look at the back of my camera, it’s upside down and backwards. And that’s exactly what I record.”

She shows me an incredible image she captured of a man who came to cut down a tree in her yard, an image that ended up being unusable due to an issue with the varnish in the final steps of development. In order to shoot any sort of analog photography you need to make an educated guess about exposure and cross your fingers that what ends up in your hands looks anything like what you see through the viewfinder. After all the fussing and nerves, you’re left with one beautiful thing that so clearly reflects the blood, sweat and tears that come with perfecting a skill from the seventeenth century.

She shows me an incredible image she captured of a man who came to cut down a tree in her yard, an image that ended up being unusable due to an issue with the varnish in the final steps of development. In order to shoot any sort of analog photography you need to make an educated guess about exposure and cross your fingers that what ends up in your hands looks anything like what you see through the viewfinder. After all the fussing and nerves, you’re left with one beautiful thing that so clearly reflects the blood, sweat and tears that come with perfecting a skill from the seventeenth century.

The point between: Karen Faris“Digital photography changed the landscape. I would never have entered any of this if I had to use film,” shares artist Karen Faris as she holds up a piece of her work for me to see in its full gravity. A huge swathe of semi-sheer chiffon fabric explodes with color without allowing the viewer to find a rhyme or reason. Somewhere between abstract art and ornately printed fabric you can find Faris’s analog collage creations digitally printed on panels of fabric.Faris is what I would call an artist with a capital A. You can tell immediately upon meeting her that something inside her radiates the need to create from the inside out. She identifies as a poet and a visual artist who also dabbles in performance art; in fact, several of her printed fabric pieces were involved in a performance she recounts to me.Her finished fabric pieces gain new light when Faris describes her process, each one completely unique and impossible to replicate. What appears to be an enigmatic composition of color is a photo of a wooden door that she has taken. She then inverted the colors, printed out the image, and collaged on top of it. She will rephotograph it again and often repeat this process multiple times including new materials, such as tissue paper, ink, flowers, moss, and text from her own poems. When she’s reached a place where she’s happy, she will photograph the final work and have it printed on fabric.“It’s in that point between: it’s not too abstract and it’s not representing.”

The point between: Karen Faris“Digital photography changed the landscape. I would never have entered any of this if I had to use film,” shares artist Karen Faris as she holds up a piece of her work for me to see in its full gravity. A huge swathe of semi-sheer chiffon fabric explodes with color without allowing the viewer to find a rhyme or reason. Somewhere between abstract art and ornately printed fabric you can find Faris’s analog collage creations digitally printed on panels of fabric.Faris is what I would call an artist with a capital A. You can tell immediately upon meeting her that something inside her radiates the need to create from the inside out. She identifies as a poet and a visual artist who also dabbles in performance art; in fact, several of her printed fabric pieces were involved in a performance she recounts to me.Her finished fabric pieces gain new light when Faris describes her process, each one completely unique and impossible to replicate. What appears to be an enigmatic composition of color is a photo of a wooden door that she has taken. She then inverted the colors, printed out the image, and collaged on top of it. She will rephotograph it again and often repeat this process multiple times including new materials, such as tissue paper, ink, flowers, moss, and text from her own poems. When she’s reached a place where she’s happy, she will photograph the final work and have it printed on fabric.“It’s in that point between: it’s not too abstract and it’s not representing.”

Her work contains fragments of text and photographs but doesn’t tell a story in the same way a painting or illustration of a garden of flowers in the park might. Instead, you get a photograph of flowers from the park that have been printed and painted over and photographed again with more real flowers on top, a splatter of ink and a pile of text cut from a poem, then printed on a panel of chiffon that lets the light through just enough to bring magic to the moment when you’re viewing it. Faris insists over and over that she hasn’t been taught to draw, doesn’t yet know how to sew, and barely knew how to use a digital camera when she began to experiment with this process. While these roadblocks could so easily deter a person from exploring visual art, Faris treads strongly forward, grabbing what she can get her hands on and weaving it together to redefine the idea of “photography” from the inside out.

Her work contains fragments of text and photographs but doesn’t tell a story in the same way a painting or illustration of a garden of flowers in the park might. Instead, you get a photograph of flowers from the park that have been printed and painted over and photographed again with more real flowers on top, a splatter of ink and a pile of text cut from a poem, then printed on a panel of chiffon that lets the light through just enough to bring magic to the moment when you’re viewing it. Faris insists over and over that she hasn’t been taught to draw, doesn’t yet know how to sew, and barely knew how to use a digital camera when she began to experiment with this process. While these roadblocks could so easily deter a person from exploring visual art, Faris treads strongly forward, grabbing what she can get her hands on and weaving it together to redefine the idea of “photography” from the inside out. In some ways Faris and Libby appear to be on opposite ends of a spectrum. Libby toils endlessly to set herself up for success, but when it comes down to it she has fifteen or so minutes between the snap of the shutter and revealing the final image before her. Between the light, exposure, and chemistry it seems like a fight against the elements to get the perfect ambrotype or tintype, but in that moment when the image reveals itself, it looks like a moment stolen from history that takes your breath away.Faris’s process takes time, but it is also furiously quick. There are no mistakes. Faris doesn’t use photoshop to edit out mistakes or dirt from her flowers, every element that lands on her page becomes a new thing to play with. There’s always another way to push the work when it’s not quite scratching the itch—print it again, cut it apart, throw moss on top, photograph it again…“It doesn’t matter what art form you’re doing.” Faris says. “It’s all about storytelling.”

In some ways Faris and Libby appear to be on opposite ends of a spectrum. Libby toils endlessly to set herself up for success, but when it comes down to it she has fifteen or so minutes between the snap of the shutter and revealing the final image before her. Between the light, exposure, and chemistry it seems like a fight against the elements to get the perfect ambrotype or tintype, but in that moment when the image reveals itself, it looks like a moment stolen from history that takes your breath away.Faris’s process takes time, but it is also furiously quick. There are no mistakes. Faris doesn’t use photoshop to edit out mistakes or dirt from her flowers, every element that lands on her page becomes a new thing to play with. There’s always another way to push the work when it’s not quite scratching the itch—print it again, cut it apart, throw moss on top, photograph it again…“It doesn’t matter what art form you’re doing.” Faris says. “It’s all about storytelling.”

Views: 5