It was a different world in Rochester at the dawn of 1925. Up until a few years earlier, the Erie Canal ran through downtown. Now, it’s been newly rerouted and renamed the Barge Canal, wrapping around the city’s southern border. Only weeks earlier, Broad Street, the now-familiar thoroughfare that runs on top of the old canal bed, crossing the Genesee at the old aqueduct was completed. Already under construction was the seven-mile-long Rochester subway, which ran in part under Broad Street on the canal bed but wouldn’t be up and running until 1927.

We were known back then as the City of Inventions, routinely leading the state in patents per capita. Radio was in its infancy. Rochester had one station, WHAM, which had been on the air for six months. Programming consisted of six hours a day of performances by the Eastman Theatre Orchestra plus ten minutes of weather and market reports.

At the Eastman Theatre, the Rochester American Opera Company was presenting Faust. At Fays Theatre on West Main, later known as the Capitol, the bill was a combo of Mack Sennett comedy shorts and six live vaudeville acts.

The most popular show in town was the new silent picture just opened at the Regent Theatre, A Sainted Devil, in which heartthrob Rudolph Valentino was searching the land for his stolen bride and her abductor.

But on January 25, 1925, the most anticipated show in Rochester wasn’t on a silver screen. It was in the sky.

Total eclipses are not a rarity. They occur about six times every ten years. But each is visible only along a narrow swath of Earth. Rochester’s previous total eclipse was in 1806, when clouds rolled in and ruined the show.

In 1925, the path of totality began just west of Duluth, Minnesota, and covered a 100-mile-wide strip to the Atlantic Ocean at New York Harbor, a slice that passed over Rochester. Local astronomers bragged that their methods of prognostication were so precise that the predicted “zone of totality” would be accurate “within a mile or two.”

Today we know that looking directly at an eclipse is unwise, regardless of what you look through, but in 1925 the popular filters were smoked glass and dark photographic film. Although there were warnings even then that this wasn’t safe, demand was huge—so much so that there was a shortage of dark film and smoked glass as the Flower City readied to be dazzled.

During the weeks before the eclipse, the morning newspaper ran an ad for an item that would allow readers to view the eclipse “without injuring your eyes.” The device was called “Indeveico Deffecto,” a name that doubled as a disclaimer. Dark film in cardboard frames, they sold for ten cents each or six dollars for 100. Readers were told to send their money to an address in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

As this was the first total eclipse in Rochester since the invention of the horseless carriage, drivers of automobiles were asked to stay off the roads during the eclipse. During totality it would grow too dark to drive without headlights, and headlights were seen as a hindrance to viewing the spectacle.

Along the same vein, Rochesterians were asked to keep the lights off in their homes and offices during the eclipse to maximize the amazing darkness. In the city, streetlamps would be kept extinguished.

By 1925, Rochester already had a robust history in optics, physics, and probing the mysteries of the universe. Professor S. A. Mitchell of the American Astronomical Association planned to take advantage of the city’s first total eclipse since the very Rochestarian miracle of photography. Scientists were hoping to capture the best images yet of the glowing halo of the sun’s corona, which extended millions of miles from the sun but was only visible during an eclipse.

“We’re hoping after we measure the intensity of the light, measured and analyzed by spectroscopes, we may endeavor to find out just what it is,” Professor Mitchell said.

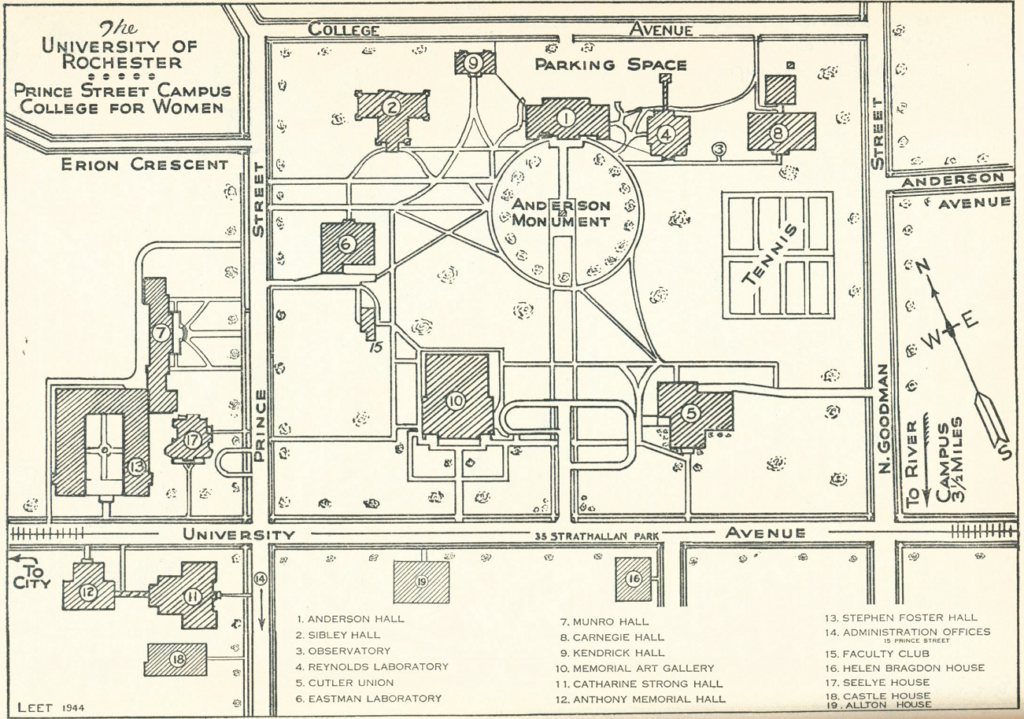

At the University of Rochester, term finals were delayed so that everyone would have an opportunity to see the eclipse. A group of physics students under the tutelage of Professor Henry Lawrence, made elaborate plans to photograph the eclipse from the campus’ Trevor Observatory.

Today, the university has a state-of-the-art observatory at its disposal in nearby Naples. In 1925, the observatory was more modestly sized, a small dome next to Reynolds Lab on the Prince Street Campus housing a telescope with a six-inch object glass.

For the second half of the nineteenth century, the best place to watch the stars had been the Warner Observatory on the south side of East Avenue, but it was abandoned and boarded up in 1920.

U of R science students set up equipment to measure the brightness of the sky at the stages of eclipse, and the character of the “general illumination.” Others measured variations in the direction and intensity of earth’s magnetic field.

A group from Harvard University came to Rochester to study the eclipse at the Bausch & Lomb observatory at Lowell and Martin Streets. Scientists from the Eastman Kodak Company were also camped out at the Bausch & Lomb factory, ready to photograph the phases of the eclipse through smaller telescopes mounted in windows.

Two other groups prepared to measure, respectively, the effect of the eclipse on gravity and upon the transmission and reception of wireless radio. Both WKBW in Buffalo and WHAM in Rochester planned special broadcasts during the event to facilitate the experiments. Another group of radio operators and broadcasters, along with laboratory specialists, prepared to measure the effect of the eclipse on electromagnetic waves, known at the time as “ether waves.”

In Henrietta, folks were urged to watch the eclipse from the top of Methodist Hill, where, if conditions were right, the shadow of totality on the Earth would be visible, approaching at a frightening speed—1,300 miles per hour.

This being the end of January, everything was frozen, with temperatures dipping below zero every night, so spectators planned their viewing to the minute. The 1925 eclipse would begin at 8:00 a.m., totality would be reached at 9:09 a.m., and the eclipse would end at 10:26 a.m. Because of the wintry date and early morning time, the sun would be low in the sky at showtime. Not that it mattered…

The enemy of all eclipses is a cloudy sky. Clouds ruined the total eclipse of 1806, and they did it again in 1925. Reading the next day’s papers, it was easy to tell which headlines were written before the eclipse, and which after:

Before: “Phenemenon awes humans, birds and beasts; Thrills fish.”

After: “Folks are disappointed when clouds obscure sun.”

The young scientists at the Univerisy of Rochester didn’t get to take their photographs.

Clouds couldn’t completely stop science, though. The experiments regarding wireless radio and gravity went on as planned—and elsewhere in the country, the US military allowed top astronomers to fly in army planes over the clouds and photograph the eclipse.

Despite the clouds, new information was learned. For one thing, it had long been known that a shortwave radio’s broadcasts increased in strength during the day and dwindled at night. During the totality of the eclipse, shortwave communication shrunk just as if the sun had set. Longwave radio signals, on the other hand, which normally got only as far as Geneva, during totality could be picked up in Schenectady.

WHAM radio ran an experiment and learned that totality caused a “violent agitation, as large as three degrees” in the direction of its tone wave.

In areas where the sky was clear, which included a strip along the Southern Tier of New York State, a number of people, to use a modern term, freaked out during the eclipse. Those sensitive to the changing conditions described a “peculiar feeling creeping up and down their spines,” especially when it grew so dark that stars were visible in the sky. When it was over, mental anxiety all but evaporated, but there was also a rise in medical complaints, with scorched corneas and stiff necks being the most common.

While it was cloudy in Rochester for the big event, there was a timely spell of clear skies at Niagara Falls. Even as black clouds approached, the eclipse transformed the falls’ “cataract” into a sparkling dance of visual delights, a magnificent kaleidoscopic display. The eclipse, witnesses said, transformed the falls’ spray into eerie gleaming lights, glowing and pulsing through the prismatic surfaces. Then, less than a minute before the moment of totality, the clouds came and the light show was over.

The good news for the Buffalo area is that in 2024 the Horseshoe Falls are again in the eclipse’s path of totality. In Rochester, clouds have won twice in a row. This year, it just has to be clear and sunny on total eclipse day. We are due!

Note from the author: This article could not have been written without the cooperation of University of Rochester media relations director Peter Iglinski.