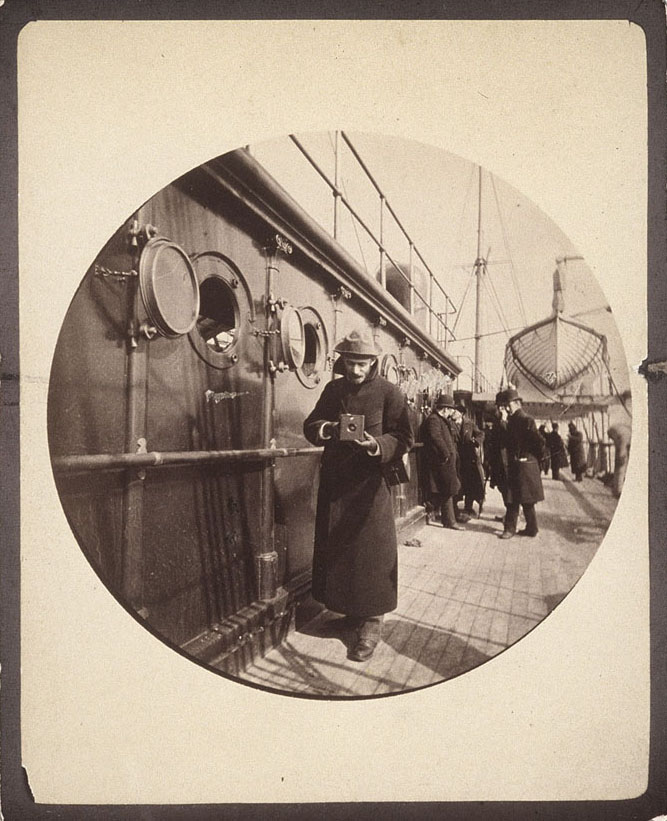

More than ninety years after his death, the legacy of iconic entrepreneur, inventor, and founder of Eastman Kodak, George Eastman, lives on in Rochester. Known as “the father of popular photography,” Eastman created a dry film that was both transparent and flexible, simplifying what was previously a complex print-making process and increasing its affordability for consumers.

His first mass-marketed camera, the Kodak Camera, cost $25 when it was released in 1888. A decade later, in 1900, Kodak created the Brownie Camera, which retailed at a mere $1.25.

Following Eastman’s death in 1932, his sprawling, Georgian-style mansion was left to the University of Rochester (UR). Because the property was so expensive to maintain, Eastman’s colleagues at the university decided to have it turned into a museum celebrating the pioneer of photography’s enduring legacy.

Accordingly, the George Eastman Museum was established on the 8.5-acre East Avenue property where it remains to this day, drawing in thousands of visitors (to both the museum and the house) each year.

The fully restored George Eastman House opened to the public in 1990.

Visitors to both the George Eastman House and the museum will encounter countless photographs, cameras (including the first digital camera), art documentation, and more than 200,000 other historic objects related to both George Eastman’s personal life and his career of innovation.

Todd Gustavson, the George Eastman Museum’s curator of the technology collection and an acclaimed author, has worked for the museum since 1997 and can speak to the corporation’s many impacts on Rochester’s economy.

“George Eastman believed in treating his employees well,” says Gustavson. “[Eastman] Kodak [est. 1888] had collection boxes where workers could submit their ideas, and, if the management thought they were high quality, people would be paid for their suggestions.”

He notes that while Eastman acquired several smaller companies throughout his meteoric rise—and was not always well-liked by competitors—his business model was largely unparalleled. Often, when CEOs take over less-established organizations, the boots-on-the-ground workers get pushed out. Eastman’s investment approach was to keep the materials and the laypeople he employed, changing out the management instead.

“George Eastman had a hand in helping Rochester locals purchase homes and cars, the development of pensions, wage dividends, and retirement accounts,” says Gustavson.

Not only did Eastman ensure his employees received financial benefits, but he invested in his community, too. Ever the philanthropist, Eastman funded UR’s Eastman School of Music and School of Dentistry, Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO), the Center for Government Research (formerly the Bureau of Municipal Research), ESL Federal Credit Union (formerly Eastman Savings and Loan), the Eastman Dental Dispensary, and several local parks.

He is also credited with founding the United Way (formerly the War Chest) and starting a local chapter of the American Red Cross.

In addition to his regional efforts, Eastman supported education and research on a global scale by making sizeable contributions to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Tuskegee University (formerly the Tuskegee Institute), Hampton University (formerly the Hampton Institute), and the University College of London.

Kathy Connor, curator of the legacy collection at the George Eastman Museum, manages the restoration of the George Eastman House along with an archive of items preserved from throughout George Eastman’s life (1854-1932). The collection, which is housed in the attic of the Dryden Theatre, contains everything from Eastman’s camping and hunting gear to the tablecloths he used when entertaining (stains and all!) to early versions of Kodak’s marketing materials and annual reports.

But, as Connor will be quick to tell you, while Eastman’s contributions to the photography and motion picture industries are far-reaching, his influence on the city’s heritage extends beyond the arts.

“You can’t go more than a mile [outside the George Eastman House] without seeing something that was either founded by or funded by George Eastman,” she says.

And much of what Eastman built was for the benefit of others.

Connor says, “Eastman created parks [like Durand Eastman Park] so that his employees had somewhere to take walks, and he built his dental and medical facilities so that workers needing emergency services did not need to travel far to get help.”

“Ultimately, [Eastman] wanted to make Rochester a good place for people to live and raise a family,” adds Connor.

The self-educated innovator also hoped to develop a worldwide manufacturing business, and, in founding Kodak, he was able to do exactly that. By 1988, it was estimated that one in ten Rochesterians worked for the corporation, making it the largest employer in the area.

Eastman’s ashes are housed in the Eastman Business Park at a memorial that is open to the public. There, the Kodak founder is represented through a monument that depicts his core values—intellectual ambition and science—via two large carvings on a marble pillar.

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2023 issue of (585).

Views: 19