During the fall of 1900, twenty-six-year-old Teresa “Tessie” Keating worked at Brownell’s Camera Works, at the current site of the Kodak Tower, and lived at 171 University Avenue with her widowed dad and two sisters. A third sister had recently moved to Rochester and was looking for a housekeeper. Reading an ad in the paper, Tessie decided—on her own—to do her sister a favor and visit the prospective servant, a Mrs. Alice Herbert, at her home in a rooming house on Rochester’s Davis Street. It was drizzling and she tugged on her rubbers and grabbed an umbrella on her way out the door.

Tessie left home between 7:10 and 7:15 p.m. on Tuesday, November 20, 1900, unaware that her destination was a haven of ruffians, a bricked gangland where the “Goat Hill Gang” was in charge.

The walk from home to the Davis Street address took only seven to ten minutes. While newfangled electric streetlamps burned in the distance, it was very dark on Davis Street as Tessie searched for the address. Too dark to see your hand in front of your face—but she could hear footsteps . . .

At 10:30 the next morning, seven-year-old Philip Spuck of Union Street was looking for scrap metal in an abandoned yard behind a billboard at Davis and Union streets when he came upon a woman’s hat, then an umbrella, and then a woman’s rubber overshoe. The boy picked up the items, took them home, and showed them to his mom, Pauline.

She was most impressed by the rubber. “This looks brand new. Go back and see if you can find the other one. Take Edward with you,” Pauline said.

Philip grabbed his twenty-year-old brother, Edward, and, after waiting out a brief downpour, they returned to the spot behind the billboard.

Then Edward saw something in the weeds.

“Philip, you go home now.”

“But, I—”

“Just do it,” Edward spoke sharply.

“Oh, all right.” Philip moped away.

Edward tentatively approached the thing in the weeds and confirmed it was a young woman, hard up against the back of the billboard. He hoped she was just a drunk, but no. Blood and white froth came from the nose and mouth. Protruding tongue. Blank stare. Bruised face. Thighs open. Fingermarks on the throat. Dressed in a brown bicycle skirt, pink shirtwaist, and brown fedora hat.

Registering the horror, Edward ran and ran until he found detective William F. McGuire on nearby Hartford Street. Together, they returned to the body. After police combed the area, the body was taken to the morgue and autopsied. She’d been raped. Cause of death: strangulation. It was the twenty-ninth murder in Monroe County history.

Police rapidly identified the body; Tessie’s family had reported her missing at 1:45 a.m. After talking to the family— ”Tessie never caused any worry”—police went to the rooming house that had been her destination.

The landlady there, Mrs. Nora Crowe, verified that Tessie had arrived and been sent away.

“Mrs. Herbert wasn’t in,” the landlady said. “Last I seen the girl she was heading toward Union.” And the billboard behind which her body would be found.

That all fit. Problem was Mrs. Crowe was acting suspicious. She said Tessie came to the house at least an hour later than had been thought to, and when questioned about the identity and whereabouts of her other tenants the previous night, she hemmed, hawed, and spoke in circles.

It took police many man-hours to sort it out. Mrs.Crowe’s tenants were a bunch of ne’er-do-wells, gang members, small-time criminals, drunks, and vagabonds. Finding out where they all were and what they were doing at the time of the murder was quite a task, but once completed led investigators to believe none of them were the killer.

The case was sensational and brought out the loonies. Oddballs confessed to things they didn’t do. Some claimed to see things they didn’t see. Some were lying. Others were just wrong.

The first attempt at a Requiem Mass for Tessie at Corpus Christi Church on East Main was canceled because of an inability to control the crowds. Tessie’s remains were buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery (Section E, Alphabet Plot, Grave 7) without ceremony.

The mass wasn’t offered until December 4. Enough time had passed that the funeral was peaceful, but there were still 100 strangers there, quietly paying their respects to a young woman they only knew because of her notorious death.

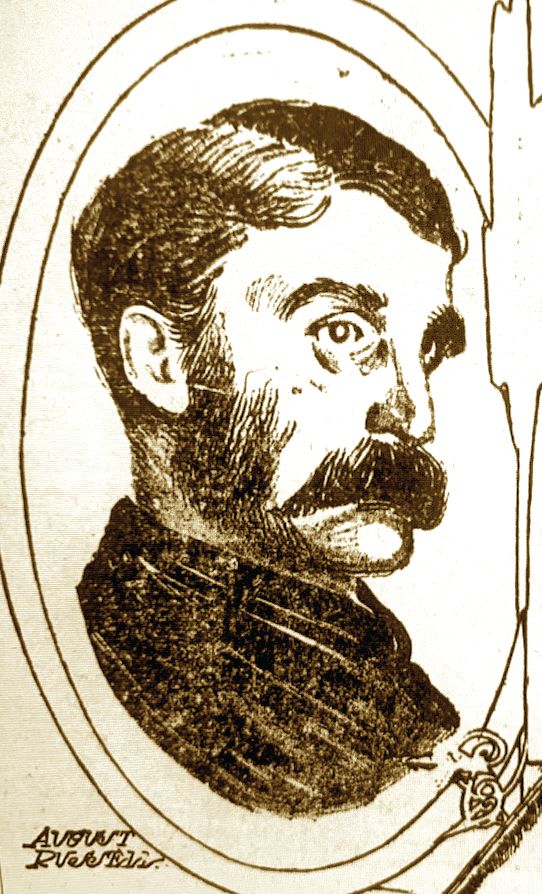

The crime remained unsolved for two and a half years. On June 9, 1903, August Russell, forty, of 74 Henrietta Street, was arrested on a tip from his wife.

“He was beating me one day, and I said, ‘You must be the man who killed the Keating girl.’ And he stopped hitting me and he thought a minute and he said, ‘Yes, I am.’ After that I wormed the whole story out of him bit by bit,” Mrs. Russell said.

Russell was arrested at the corner of Broadway and Monroe Avenue. As one policeman engaged Russell in conversation, pretending he could get him work on a farm out in the country the other sneaked behind Russell and clapped a heavy hand on his shoulder.

“I arrest you for the murder of Theresa Keating,” McGuire said.

Russell bowed his head and said: “I didn’t mean to kill her.”

Russell was physically peculiar. The upper portion of his skull was perfectly round, a fact later confirmed by a doctor’s calipers, and he loved to adorn that billiard-ball head with ladies’ hats. He was five-five, slight, with deep creases in his forehead, a nervous fidgety disposition, and freakishly long arms that hung to within an inch of his knees. He had one light blue eye and one dark brown eye and walked through life with a perpetual squint.

Police learned that Russell, at the time of the murder, lived in the Empire Hotel on Front Street, registered in his own name. Front Street ran north from Main along the Genesee’s west bank, and until it was razed for urban renewal, was a magnet for bums and transients. On the night of the murder, Russell got drunk— ten whiskeys and a bucket of beer—in William Carrington’s Saloon.

Suspecting a false confessor, Chief Hayden introduced erroneous details about the crime.

“Now the victim was found with her gloves on,” Hayden said.

“No, she wasn’t,” Russell immediately replied. “I don’t know where they were, but they were not on her hands.” In reality, the gloves were found stomped into the mud some feet from the body.

“Would you be willing to come with us to the crime scene and show us how it happened?”

Russell said he would and led the policemen to the billboard on Davis Street and pointed out different spots with unfailing accuracy. He showed them the place on the sidewalk where he confronted the victim. He made the young woman an improper proposal.

According to Russell, she replied, “Go away, you dirty loafer.”

He lost his temper, hit her on the temple and choked her. When she was unconscious, he dragged her off the sidewalk and into the vacant lot. He said that he remained in the lot with Tessie for three hours. He left about midnight.

“I took her pulse to make sure that she was still alive,” he claimed.

After leaving the lot he walked to Main Street, then to Front Street, where he took a bed in one of the fleabag hotels there. The next day, he skedaddled to Irondequoit.

Russell was indicted on October 30, 1903, after a grand jury recommendation, and arraigned on the morning of November 14, before Justice Nash. He pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. A commission was appointed, two doctors and a lawyer, to inquire into Russell’s sanity.

The hearings involved calling witnesses. Some men who knew Russell thought he was demented, but others— especially when discussing Russell’s handling of money—thought him sane as the day was long. All agreed that Russell was at his weirdest when around women.

“If a woman spoke to Russell, he would follow her home, and she would find it impossible to get rid of him,” one witness said.

On New Year’s Eve 1903, the insanity panel declared Russell insane. Russell was taken directly to Matteawan State Insane Asylum, a then-new facility, where he was to be confined until declared sane. Of course, there was no guarantee that would ever happen.

“I’m the magic man. I hear music when you do not,” Russell said, as he headed for his padded cell.

Once inside, he became a patient who laughed. Some guys screamed in terror all night or yelled angrily. Russell was a laugher.

He did eventually get out of Matteawan. Some say he relocated to the Catskills and died in Ulster County.

Davis Street is only slightly different today than it was in 1900. It dead ends at the railroad tracks, now Amtrak. Back then, Davis Street continued south of the tracks and went through to Union Street. The large building for Ametek Power Instruments, where they make monitors to measure and maintain power grids, now sits where the easternmost part of Davis Street used to be and covers up the crime scene.

Michael Benson is the author of Filthy Murders of Ye Olde Rochester.

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2025 issue of (585).

Views: 37