Photographs, film, and video have been used to document important celebrations both big and small for years— births, birthdays, weddings . . . these mediums have created a way to not only preserve moments but create history as well. However, something so crucial about this form of archiving is that it doesn’t keep images safe forever— film, cassettes, and video deteriorate, and that’s where Preserving the Past steps into the frame (no pun intended). Founder and president Taylor Whitney started the company in 1997 after spending years working in the film production and preservation industry in Hollywood, California.

(Little fourth wall break—for readers who were born in the 1990s or later, the motion picture film being referred to is the kind spooled on reels that your grandpa would have hooked up to a projector. While you may not have used this film yourself, there’s a good chance someone in your family has boxes of it sitting in their attic with stored memories you may have never seen).

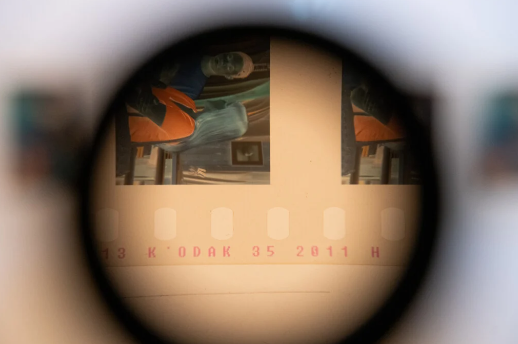

Most movies from the 1920s into the 1980s were shot on a film coined “safety film,” created to replace the previously popular yet combustible nitrate film that caused a number of fires and deaths. “Safety film” had an acetate base, which eliminated the flammable hazard but was also found to deteriorate. The term “vinegar syndrome” may sound familiar.

“When the acetate deteriorates, the film shrinks, loses color, the emulsion strips away, and it produces a pungent vinegar smell,” Whitney says.

Warm and humid conditions accelerate this process, and, once it starts, it progressively advances unless proper measures are taken. Cold storage helps preserve the film and significantly decreases the chance of vinegar syndrome starting and drastically slows the process after it’s begun.

In the 1990s, Whitney was working as a senior film inspection technician and a senior film librarian at a facility that specialized in cold storage for film deterioration. Polyester film—Kodak’s ESTAR film—was becoming predominate as “safety film” was phasing out. Corporations would have their acetate film recreated on polyester, and Whitney would inspect the polyester film, making sure there weren’t any errors before it was put into cold storage. She worked on restoring major motion pictures such as Vertigo and other Alfred Hitchcock films; the Sammy Davis Jr. collection; the Michael Douglas collection; Mary Pickford films; and others from MGM, Disney, and Paramount, ensuring they could be pulled out of storage in thirty years without any issues.

“While I was working on these pictures, a lot of attention was being paid to major motion pictures and not a lot of attention was given to what I call cultural collections,” Whitney says. “The collections that are in country clubs, churches, museums, families, businesses, and libraries. That was the impetus for starting Preserving the Past, because I thought these other collections deserved to be preserved according to preservation standards.”

While motion picture film may have steered Whitney’s business journey, Preserving the Past offers many other different services that are just as important.

A process that will hit close to home for many is video digitization. Nineties friends, this refers to the video tapes your parents recorded your childhood on—think Hi8 or MiniDV, gray-and-black chunky hand cameras, and grainy, date-stamped home videos. Setting aside that this has become a modern vintage aesthetic—any magnetic tapes, including Betamax and VHS, deteriorate, and they do so much faster than motion picture film.

“Video became quite popular in the late seventies, eighties, and nineties and phased out in the 2000s, and the signs of deterioration are monumental,” Whitney says. “I would say get them digitized if you want to save those memories, celebrations, and anniversaries. A lot of fiftieth anniversaries were shot on video [as well as] a lot of births. When video first started, they brought video cameras into the maternity ward. If you’re at thirty years with your video, it’s important to start thinking about getting it digitized. Film started transitioning in the forties, and we noticed deterioration in the eighties, so about fifty years for film in normal storage. But if the film is being kept in a cool and dry environment, the video would take priority.”

Families, however, are only some of the clients Preserving the Past provides services to. It works with museums, businesses, corporations, churches, institutions—a variety of groups. When working on digitization and restoration projects, they aid in color restoration, editing, and conversion of standard definition (SD) footage to high definition (HD). After completed, the projects are stored on external drives to deliver uncompressed, professional-broadcast quality footage to the owner.

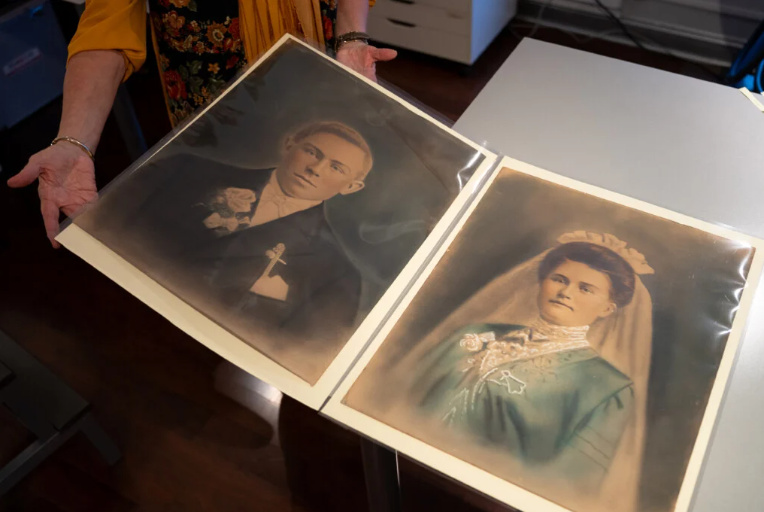

“We won the contract to digitize nine hours of footage from the discovery of the Titanic for the hundredth anniversary of its sinking,” Whitney says. “It was the moment people saw the Titanic for the first time, and their voices and what they were saying; it was amazing footage. They had more than 600 videotapes and film elements that were SD, and we rendered all of it to HD.” Whitney and her team offer services for photographs, paper documents, and 3D artifacts, as well. Each collection brought in—film included—goes through an elaborate cataloging process Whitney refers to as the seven stages of archiving. This makes it easier for the owner to not only look through their items but to grasp an understanding of what they’re looking at.

“Every piece gets its own number, and when we digitize it, that number matches the original,” Whitney says. “People bring in their photographs or Civil War letters, and the first stage is getting a sense of the collection and separating it out if there are different elements. When we did the Brighton Fire Department, it had everything from videotapes to photographs to fire hoses to uniforms to negatives and slides and framed objects like statues and badges that were on display. Then if you’re looking at images on the hard drive, they can always be referred back to the original. We don’t just take a box of photos, scan them in, and hand them back—they’re organized, numbered, labeled, and rehoused.”

Repairing tears and cracks as well as restoring color is essential for a multitude of mediums, and Preserving the Past strives to keep artifacts genuine.

“We really look at the paper and the tone—the essence of the photograph— and try to capture and honor the authenticity of it and maintain its trajectory through time. If it’s a photo from 1940, we don’t want a restored photo that looks like it’s from 2010,” Whitney says.

Preserving the Past takes the preservation process one step further and offers state-of-the-art cold storage for anyone. It costs five dollars per cubic foot of space a month, is kept cool and dry at 45 degrees Fahrenheit and 25 percent relative humidity, has 24/7 monitored security, and is ten stories underground.

“Film, video, and photographs are deteriorating as we speak. If you put them into cold storage, it can prolong their life for hundreds of years. The University of Rochester is putting about 350 boxes in our cold storage right now,” Whitney says.

With the evolution of technology, preserving, archiving, and restoring important moments is a constant catch up game. But Preserving the Past continues to make history timeless. Information on all their services, as well as contact information, can be found on the website preservethepast.com.

“It’s not just the person who’s the client, it’s the trickle effect, you know?” Their parents, maybe their kids and their grandkids, and at the universities or the museums where they use work we’ve done in an exhibition,” says Whitney. “Cultural collections document our social history, and they’re culturally significant to history itself.”