Every old house holds a story—a window into a bygone time.

Lucky homeowners uncover the narrative fragments of their property’s history through memories reconstructed by relics or archival clues. Still, for many dwellings, detailed records are never found, and countless tales are left untold.

What if we could unravel the enigmas of these mystery homes, preserving their legacies and learning from the triumphs and challenges of our collective past?

This is where historians like Brighton’s Mary Jo Lanphear come in.

“As a COVID project, I sorted through two large drawers of recorded [housing] deeds dated 1920 to 1940,” says Lanphear. “Often, people are caught up in the events of the time in which they are living and have no clue about the rich history of the community and the country that happened before they were born.”

The town of Brighton—which celebrated its bicentennial in 2014—pays tribute to a complex heritage. While Brighton’s first inhabitants were members of the Seneca tribe of the Iroquois Confederacy, the land was transferred to farmers from New York and New England via the Buffalo Creek Treaty of 1788.

As Brighton moved through the 1800s, the town veered away from grain farming and made a name for itself as a specialized agricultural hub. While the 1700s had seen the popularization of log cabin homes, the nineteenth century brought simple frame dwellings, which led to an influx of wealthy homeowners.

However, affordability was not the only barrier prospective residents of Brighton faced in the early 1900s when pursuing a suburban life. Prior to the US Supreme Court’s decision in Shelley v. Kraemer 334 U.S. 1 (1948), area housing deeds regularly restricted people of color from buying in various neighborhoods. After the landmark court case, discriminatory housing deeds were rendered unenforceable across the nation.

“Right now, on a national level, we seem to be repeating some of the worst events of history and viewing them as if they were brand new phenomena,” says Lanphear. “That’s why the study of history is important. Brighton is an old town, and, although it’s much smaller than it was in the beginning (1814), it has much to be proud of nonetheless.”

Lanphear often encounters Brighton residents who are interested in exploring the history of their home.

“When I get a request from a resident [for information about a home], I start by requesting a copy of the building permit from the Office of Public Works. Then, I use suburban directories and newspaper accounts [pertaining to] the property and the owners,” she says.

Megan Kless, director of preservation services for the Landmark Society of Western New York, offers several research recommendations.

“It’s important to note that while many people want to know the history of their home, it can be difficult to find the architect or builder unless the home was built or owned by someone of great significance,” says Kless.

Kless shares that viewing the Rochester City Directories or conducting a deed search at the local county clerk’s office (if your property is more than sixty years old) can be an effective route for discovering a detailed backstory. Rochester City Directories—which are now digitized—list owners, occupations, and uses of a property, while deeds document priors and records of sale.

In addition to these suggestions, a homeowner can start their research journey by consulting a property’s abstract (if they have one). This legal record lists property owners as well as the dates when the property was bought or sold.

Other local resources include the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP) at the University of Rochester (for blueprints and building plans), City of Rochester plat maps, Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, and archive collections at the local public library.

An inquirer could also reference tax assessor documents and probate court records or hire a historic consulting expert to conduct a deep dive on their home.

Or maybe—like homeowner Danielle Tuttle and her husband, Steven—knowledge-seekers will stumble upon cornerstones of a property’s history in their own backyard.

The couple, who has lived in Stanley, New York, since 2022, reside in a Victorian-style home from the 1800s. The house features tributes to its nineteenth-century origins, including Victorian corbels around the exterior, pocket doors, an original staircase, and hollyhock flowers that have withstood the test of time.

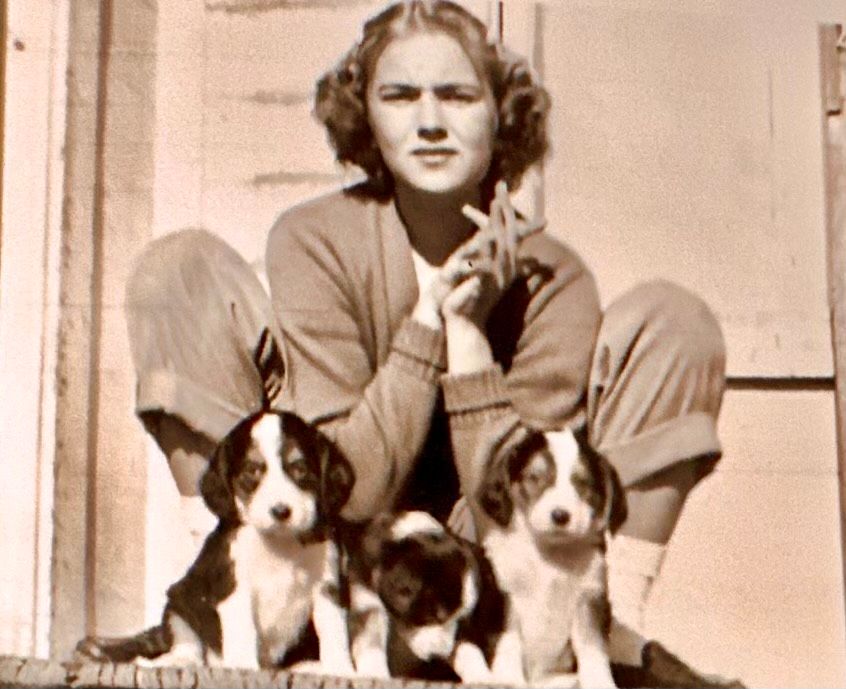

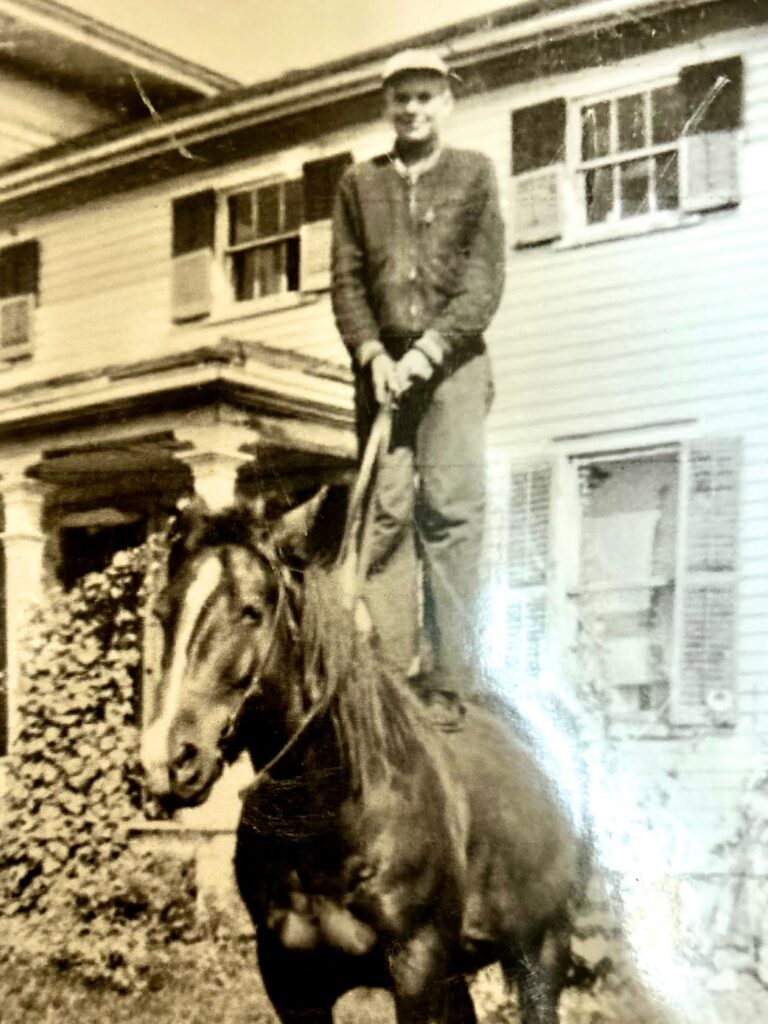

Recently, while exploring the grounds of the sprawling property, Tuttle came across old farm equipment, housewares, and black-and-white family photographs in the barn. From conversations with neighbors, Tuttle learned that she and her husband were living on what used to be a 500-head cattle farm.

“We discovered the history of our house in a really organic way,” says Tuttle. “One day, we were visited by a woman whose grandparents had previously owned the home. After we met, she started sending letters describing her childhood memories from visits to the [then] farm.”

“Even now, she regularly sends us photographs of the property as she comes across them,” Tuttle adds.

However a home’s history is revealed— whether it’s a result of research, chance, or a combination thereof—take the tale as a lesson: we often find the future in remnants of the past.

Views: 40