When I visited Joshua Enck’s studio in downtown Rochester, he was working on a twenty-one-foot, welded steel, sheet metal sculpture that, when completed, would weigh 2,000 pounds. His sculpture will be installed in front of the Imagine building at Rochester Institute of Technology in November.

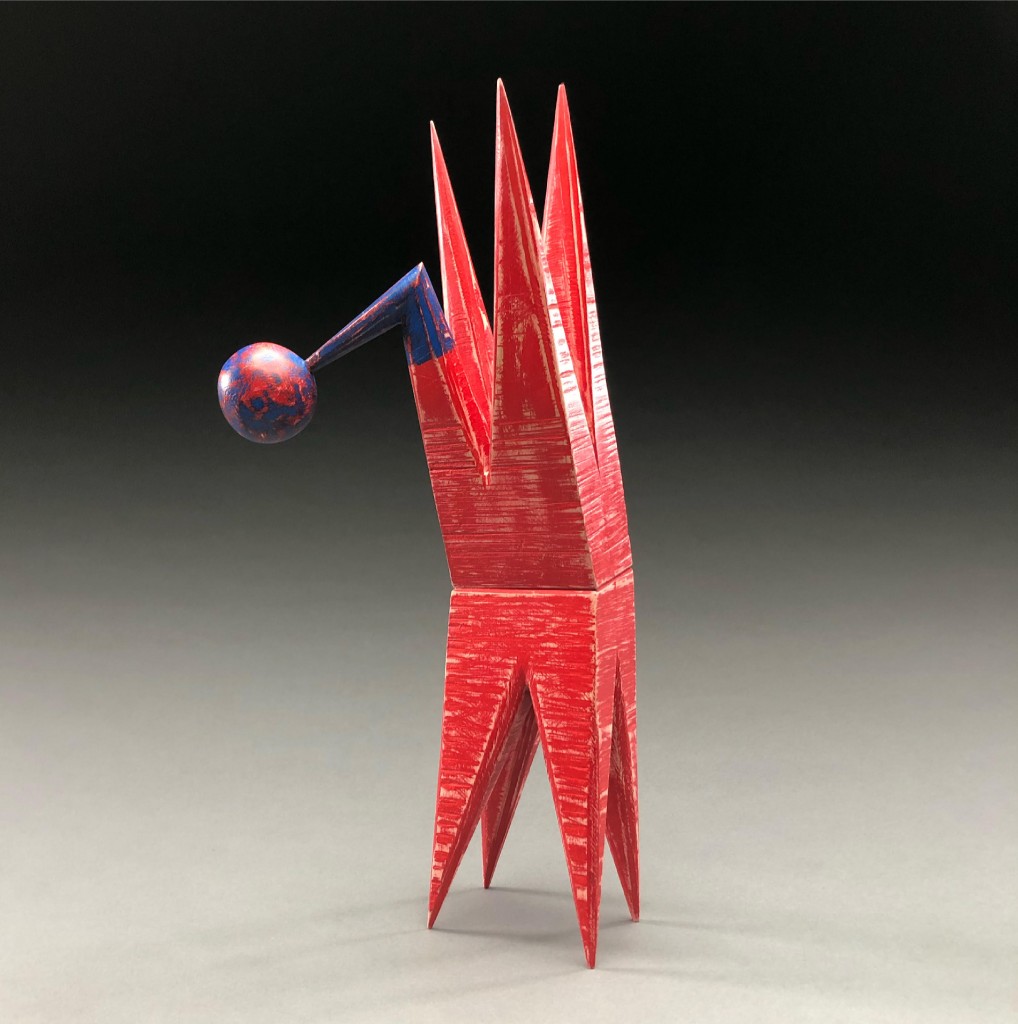

A section of the abstract sculpture was hoisted on a pulley system the size of a room. Enck pointed to a small wooden model, (which resembled a giraffe stretching its neck to see over trees) on a work table nearby, then turned toward the sculpture he was fabricating.

“These legs each weigh 200 pounds. We had originally agreed that the finished work would be twelve to fifteen feet, but it looks like it will be taller. It will have a corten finish toward the bottom—a rusting finish for steel that starts bright then turns darker—and the upper section will be painted blue,” says Enck.

“I had to rent the largest space in the building,” smiles Enck, who’s surrounded by models and museum-size sculptures in the industrial space—just one of many in the light manufacturing complex where he’s set up shop.

His space, and his work, are not the only things that are larger than life. When it comes to Enck’s background, artistic pursuit, and ideas, nothing is off the table.

Tell me about how you became interested in art.

My dad is a landscape architect who enjoys woodworking. As a kid, I’d putter around in the garage with him. I loved model trains—still do. My hobbies were woodworking and model making.

I found I liked being in a studio in high school. The high school I attended had a drafting program and a product design class and offered an introduction to architecture. That was the beginning.

I studied architecture at the University of Illinois. I loved to draw, design, and, of course, make models. After I earned my degree, a friend of mine and I built a garden shed. I realized then that I liked to make things even more than I liked designing them.

I went to grad school at Rhode Island School of Design for furniture design. I thought it would be the perfect extension of architecture.

In grad school, I was drawn more to form than function. I liked making objects that

related to the body. I remember one chair assignment; my chair had a sculptural metal base that was more like a sketch in space made from steel.The top was cast out of paper. My chair was more about how an object relates to the human body, although you could actually sit in it. I began to recognize I was more of a sculptor than anything else.

How has your training in architecture and furniture making informed your sculpture?

My approach to sculpture is about building. I work additively because my brain doesn’t conceive of form in a subtractive way. I start with a flat plane.That’s an architectural way of working.

In terms of architecture, I like vernacular forms like grain elevators and industrial shapes. I appreciate animal and organic forms too.

When I was starting out, I looked at things more consciously. I don’t think a lot about the work I do now. It’s more intuitive. I’ll sketch something and say to myself, “I’m going to start there.”

You studied for a year at an architectural school inVersailles, France, and you managed a shop at Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Colorado. What were these experiences like and how did they shape you?

Versailles was amazing. The architectural school was housed in old horse stables across from Louis XIV’s chateau in the heart of Versailles. When I first arrived, I was hoping to see buildings designed by modern architects like Le Corbusier. However, I became more interested in lesser known works by architects who designed more intimate structures.

I’d heard about Álvaro Siza Vieira, a

Portuguese architect who’d designed a teahouse on the coast and a chapel in a tiny town in the hills of Portugal. I bought a train ticket to see his work.

Another architect’s work I discovered while studying at Versailles was Swiss architect Peter Zumthor. He designed a little chapel that had significance to me because of how it relates to the human form.

I managed a woodshop at Anderson Ranch Arts Center for three years after grad school. I learned how to run a shop, to maintain machines. I love technical proficiency, handcut dovetails, etc., and that time allowed me to focus on the practical aspects of running a successful woodshop,

which has carried over today.

I think about glorifying a moment. I made a bench that just seats one. I think about connecting form and gesture. And of course, I acknowledge the importance of technical acumen in my work.

You taught at RISD for ten years, everything from woodworking and metalsmithing to technical drawing and 3-D design in its foundation program. Do you enjoy teaching?

I started teaching first in furniture design, then branched out to the foundation program for first year students. I had to come up with an entire curriculum. What do these students need to know to potentially do what I do? It was challenging and fun. I teach drawing at the University of Rochester now.

You were a Fulbright Nehru Scholar in 2018 and 2019 and spent five months teaching and doing research in India.What was that like?

I visited with craftspeople in their workshops. I observed how craftspeople there make vessels out of nonferrous materials. They work in a very traditional way, mostly with copper and brass. These craftspeople make hollow forms, often by hand, either by sinking and raising or hot annealing and hammering.

I fabricate sheet metal mostly, so I didn’t necessarily want to make what they were making. I was thinking more about their process. The people I met were using a very simple technique of snipping two pieces of metal, lapping, and soldering them. This is a technique I hope to employ in future work.

What place does art have in society?

I want art to be in people’s lives. It’s wonderful when people find ways to bring art that other people make into their daily lives. Art is a way of telling stories.Art isn’t an elitist thing. You can collect very simple things: ceramic cups, for example, or a painting that

you find somewhere in your travels.

You were selected to be a visiting artist as part of the Anna Ballarian Visiting Artist Series at RIT.The sculpture you’re completing now will be installed on the campus as part of that program.Tell me about that.

It’s a new program.Two sculptors have been commissioned, each to create a work that will be installed on the campus for three years. I will also be engaging with the RIT community. I gave an artist’s talk and had an exhibit downtown last September. I’ll also be a visiting critic at RIT.

John Aasp, director of galleries at RIT, invited me to participate. I’m grateful because it’s given me an opportunity to create a sculpture of monumental scale; something every sculptor hopes to do.

Views: 3