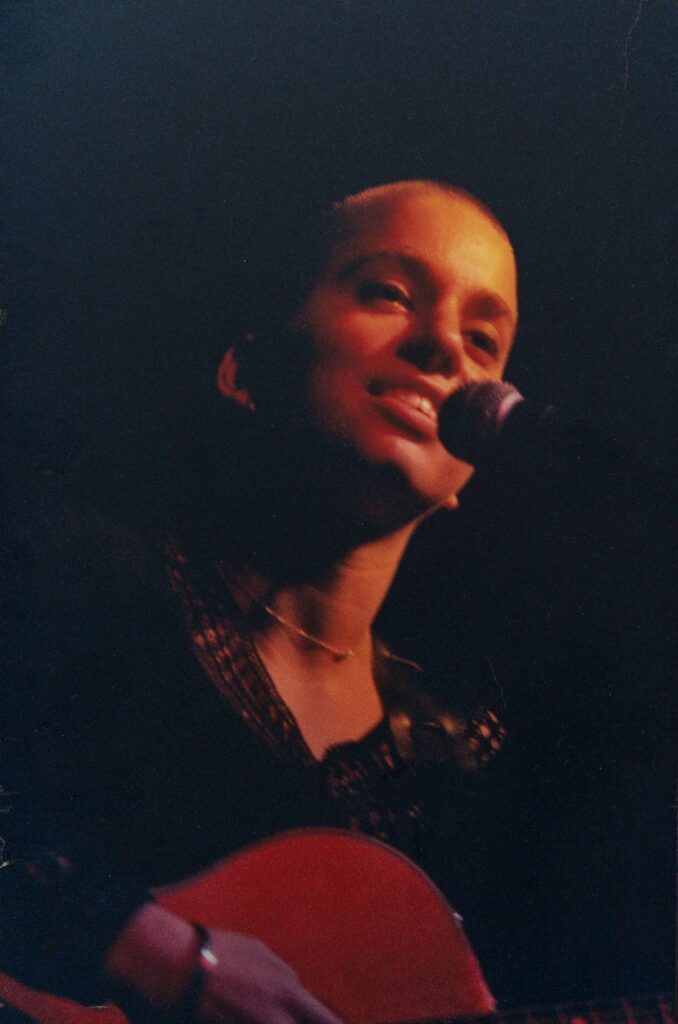

In her 2019 autobiography No Walls and the Recurring Dream, singer-songwriter Ani DiFranco recalls a story from 1990 about David Tipton, a poet friend from Rochester, who visited Buffalo for a spoken word event. He told her about a nightclub called Jazzberry’s and made the suggestion that she drive to Rochester to perform a set at the venue. DiFranco acted on Tipton’s suggestion and had a friend drive her to Rochester, and, according to Jazzberry’s owner Susan Plunkett, played to a packed crowd. After her set, she sold twenty cassette tapes, which she describes in her book as “a game changer, real money. Jazzberry’s, she writes, is a “terrific community arts space run by a cool lady named Susan Plunkett. They even cooked up good food there. Susan and her crew made sure that young artists felt welcomed and nourished.”

From 1984 to 1992, Jazzberry’s served as a cultural nerve center for Rochester, hosting an eclectic mix of musical acts big and small, plays, art shows, and poetry slams. For Plunkett, Jazzberry’s was a culmination of a culinary education and career that began as a newlywed in the mid-1960s. In those days, “I would entertain people and have parties. I started reading Woman’s Day cookbooks and started looking at cuisines from different countries. Before I knew it, I wanted to learn everything I could.” By 1973, Plunkett had divorced her husband, and, looking to support herself and two young sons, she took a cooking job at Hoosier Bill’s, a “homestyle kitchen,” then at Snake Sisters Cafe (now Lux Lounge), a feminist-minded vegetarian restaurant. In 1984, an opportunity opened up for Plunkett when the owners of the Genesee Co-Op on Monroe Avenue decided to close their vegetarian restaurant. “For a small amount, I was able to take over the place,” Plunkett recalls.

The lease was hers on one condition— the restaurant had to remain vegetarian. “I wanted to prove to people that brown rice and sprouts was not the only thing you could have.” Drawing from her experience at Hoosier Bill’s, she would rotate cuisines from different countries every week. “One week, I’d have Mexican; the next week I’d have Korean then Vietnamese then Spanish then Greek. I never wanted to be in any one place.” There was also the Jazzburger, made of lentils, mushrooms, carrots, and sautéed onions, and served with Swiss cheese, tomato, and homemade Russian dressing. It remains a staple of Plunkett’s to this day. The vegetarian cuisine brought in a diverse clientele, including cancer patients. “They would come here to eat because they wanted vegan food. I was honored that I had what they needed, and I learned a lot about it. It was very touching to me.”

Describing herself as “a jazzer” at heart, the name “Jazzberry’s” was bequeathed to Plunkett by a friend, but she knew that her new venue could not survive on jazz alone. She was interested in combining music and food and creating a “third place” where upstart bands could perform, and creativity could ferment. Plunkett’s mother, Rita Wanderman, commuted from Canandaigua and worked the front door. “I created a fantastic environment, and I am someone that just is very enthusiastic about people’s creativity. I gave them a chance. If they were horrible, I might not give them a chance, but most people were halfway okay.” In the days before social media, performers would put up posters all over the city. “I thought those posters were beautiful, and people would put them up over all the city of Rochester. That’s how they got the people to come to the venue.”

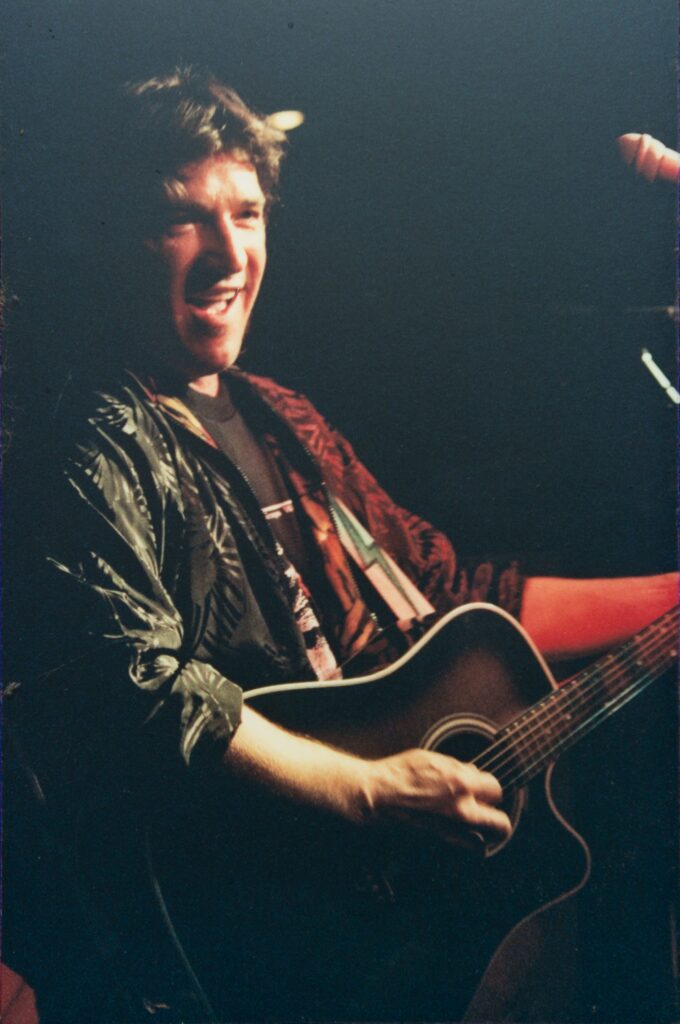

Talent from as far as New Hampshire began sending Plunkett tapes, and she made a point to learn a little about every act before booking them. Before she knew it, agents began calling Plunkett to book big-name talent at Jazzberry’s. One memorable early name talent was singer-songwriter John Hiatt, who, on Columbus Day 1986, played a show-stopping set at Jazzberry’s; later, Hiatt showered praise on Jazzberry’s to a British music magazine. Jazzberry’s was also host to a pioneering Deaf Poetry Night hosted by Peter Cook, where poems were performed in American Sign Language (ASL). “That was one of the most important things to me. I just absolutely loved that. It was so phenomenal.”

The headline performers and eclectic talent did not impress the neighbors, however, and they began to complain about the noise. Plunkett insists that the noise level “wasn’t that loud” and even had engineers monitoring the noise levels. In September 1987, Jazzberry’s had its music license revoked by the Rochester Police Department, and Plunkett spent the next several months battling the decision. “I like the music they play there, but when you’re trying to sleep at 1 a.m., it’s entirely too loud,” a neighbor told the Democrat & Chronicle at the time. In December, a protest was held at City Hall, and ninety supporters showed up. After another brief appeal, the license for the Monroe Avenue location was revoked for good at the end of January 1988. The following two years were spent in court and raising money to relocate Jazzberry’s to the East End.

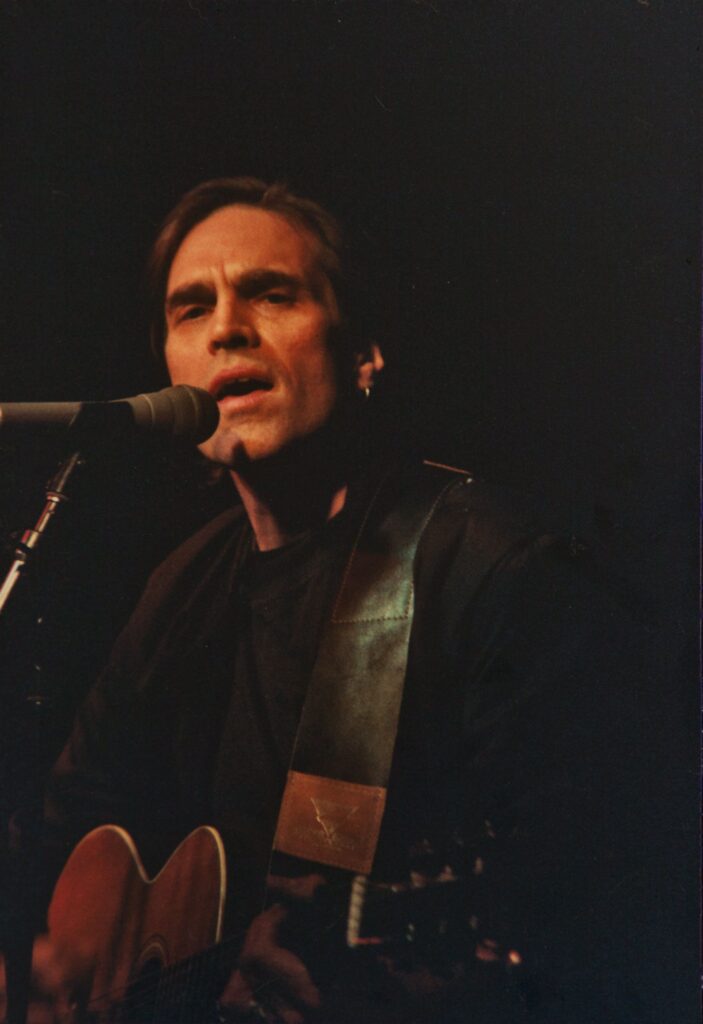

The East End of the early 1990s was not the arts and culture mecca that it is today. In the spring of 1990, Jazzberry’s Uptown opened on East Avenue. Whereas the Monroe Avenue location had a capacity of sixty-five; Jazzberry’s Uptown had a capacity of 300. “I went for the big time, and I moved downtown,” recalls Plunkett. “I helped start the East End. That’s one of my claims to fame, you know.” Through her friendship with Chuck and Gap Mangione, Plunkett was able to book Dizzy Gillespie, and, that November, he played a memorable set at Jazzberry’s, returning the following year for an encore. In 1991, Buddy Guy and Loudon Wainwright III dropped by, along with the New Mamas and the Papas featuring Mackenzie Phillips, Spanky McFarlane, and Scott McKenzie— who sang his hit “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)”—during their set. Folksinger Odetta turned in a performance that Plunkett recalls as “Unbelievable. You couldn’t hear a pin drop.” Rick Danko of The Band and Eric Andersen performed a set together with the legendary documentary filmmaker D. A. Pennebaker tagging along to capture the performance on video. Following her initial triumph, Ani DiFranco returned and performed at Jazzberry’s several more times, becoming a semi-regular performer.

For most of its existence, Jazzberry’s operated in debt. Plunkett had to pay to bring the higher profile acts, and they didn’t always recoup the costs. Even blues musicians running up tabs at the bar couldn’t keep Plunkett out of the red, and on April 29, 1992, the day after blues guitarist Albert Collins joked about being tipsy onstage, the IRS arrived at Jazzberry’s door and changed its locks. Plunkett eventually paid back what she owed, and it provided a formative lesson that she has carried into her current job as the owner of Susan Plunkett’s Fabulous Foods. Over the last thirty years, Plunkett has racked up an impressive list of regular clients, including the University of Rochester, RIT, WXXI, and the American Association of University Women. She harbors no bitterness about Jazzberry’s closure: “I’ll tell you something. It took a long time to pay my debt back, but it was worth every penny.”

Views: 80