At 6:30 a.m., Sunday, July 17, 1949, Mrs.Margaret Wagner called Greece Police and said, “A woman is lying in the grass here at Ridge Road opposite Hoover Drive.”

Fifteen minutes later, a small lifeless body was found broken in a gully in front of the Wagners’ house, beneath a fir tree, twenty-nine feet from the road. Today, the location is in front of the popular tavern TC Hooligans.

The body had been placed where it could not be seen by passing cars—but come dawn it was visible to Mrs. Wagner from her living room window.

The body belonged to Mrs. Jennie F. O’Keefe, seventy-three, of Savannah Street, just north of Monroe Avenue in Rochester. A widow, she was a seamstress for Sibley’s and mother of a Rochester policeman. Who would want to kill a little old lady—and in such a horrible way, using her and discarding her?

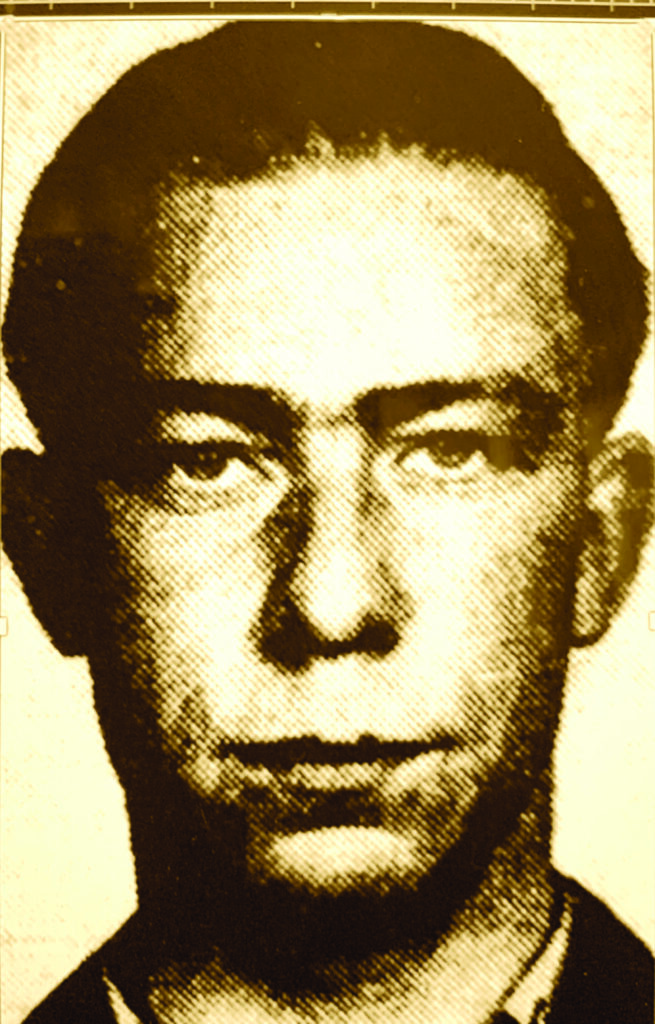

A break came early in the investigation when a local bartender said he’d seen Mrs.O’Keefe the previous evening getting into a car with a guy named William Draper, a twenty-nine-year-old laborer who lived on Oak Street, a block south of Lyell. Detectives went to brace Draper, but he wasn’t home.

At 5:30 p.m. that same Sunday, two young girls were walking along Mill Road in Greece when they found in quick succession: a woman’s girdle, some beads, a woman’s hat, and a billfold. All but the billfold belonged to Jennie O. That was Draper’s.

The site was four miles from the earlier crime scene. Along Mill Road, deputies found two sets of automobile tracks and a track that could have been made by a body being dragged. The location was remote. No houses within 500 feet. This was where the fatal attack had occurred.

Detective Bernard Daily and Deputy Leon Mosher went to the Brockport home of Draper’s mother, Mrs. Cornelia Chapman.

“He was here this morning with his wife and three kids,” the mom said. “They left, headed for friends in the Town of Sweden.”

She didn’t know the address, but she knew their name, so Daily looked it up in the phone book.

And that was where the Law caught up with Draper. He was efficiently separated from his wife and kids and placed unceremoniously in the back seat of a cop car. Fifteen hours after the body was discovered, police had their man.

Draper was taken to the Monroe County morgue where he was questioned by Greece Police Chief Milton Carter.

“I got no idea what you’re talking about,” Draper said stubbornly. He was nervous. This wasn’t the police station, and he knew it. Sure enough, the lawmen played their trump card. They pulled out the big drawer and showed him the raped and beaten corpse of Jennie O’Keefe, tag on toe.

Draper began to blubber.

“Draper, how do you know this woman?” asked fiery-eyed Chief Carter.

“I d-d-don’t,” Draper stammered.

“Where’s your billfold, Draper?”

“I, I don’t know. I lost it.”

“When?”

“I don’t know. Three, four days ago.”

Chief Carter pulled out the billfold, and Draper’s entire body slumped.

“You dropped it last night, Draper. We got you cold. Tell us, how did you know this woman?” Chief Carter asked, gesturing to the pitiful beaten body of the old woman.

“I met Jennie at Joseph Izzo’s Grill,” Draper said. Police knew that to be a joint at Lake Avenue and Spencer Street.

“You met her in a bar?”

“That’s right. I met her on Saturday morning, and she told me to return that evening, at which time she wanted me to take her home.”

If this conversation actually occurred, Jennie—a recent widow, long-married to a livery driver—did not mean what Draper thought she meant.

“What did you do all of that Saturday?” the chief asked.

“I was at my home on Oak Street. Part of the time I was working on my car with Bobby McMahon. Lives on Spencer Street.”

Cops verified this.

“Then my kid cut his lip, so I had to take him to the emergency for stitches.”

These events were also easily verified.

“After that?”

“I was ready to unwind so I went to a grill on Lyell Avenue, and I had a few drinks.”

“Get cocked?”

“No, just a few. I went home for supper, then picked up Mrs. O’Keefe in my car and drove her to Izzo’s. When we reached the corner of Savannah and George streets, Mrs. O’Keefe announced that she didn’t want to go to Izzo’s. She wanted to go for a ride.”

“So, what did you do?”

“I took her for a ride.”

“Where’d you go?”

“I took her out on Mill Road in Greece. I found a spot and parked, made my move,and she wouldn’t go for it.”

“What did you do?”

“I hit her a few times.”

“With what?”

“My fists.”

“Then what?”

“I dragged her out of the car and laid her out,” so he could continue his attack. When that was done, she was unconscious, so he carried her back into the car.

“I drove around for two hours before I realized she wasn’t breathing, that she was dead. I swear. I kept waiting for her to wake up.”

“What did you do once you realized you’d killed her?”

“I got scared. I stopped the car on Ridge Road and carried her body from the car. After that I drove to a service station on Long Pond Road and purchased a gallon of gasoline and a quart of oil. Then I went home.”

The autopsy on Mrs. O’Keefe’s body was conducted by coroner’s physician Dr. Floyd S. Winslow, who concluded that the beating had been thorough and was the cause of death.

“The entire body was brutally beaten,” Dr. Winslow reported. There were multiple contusions and abrasions over the entire body, shock, cerebral concussion, and multiple rib fractures. “She had been clawed, punched, and kicked,” the pathologist noted. “She had six fractured ribs, a crushed nose, a cerebral contusion, and bruises over the entire trunk of her body. There were more than 100 bruises over both breasts.”

Blood tests were done and determined that, at the time of her death, Mrs. O’Keefe had not been drinking excessively. Time of death was set at 4 a.m. on Sunday morning, two hours after the bars closed.

Investigators learned that Draper was a World War II vet—North Africa and Italy—although he did go AWOL. He had a surprisingly loving wife, Mabel, and three boys.

In jail, Draper paced like the caged animal he was, chain-smoking cigarettes. Draper’s wife came to the jail, distraught. Reporters cornered her and she said that she planned to stick with her man.

“He suffered a head injury in the army,” she said. “Sometimes it makes him act odd. He has a metal plate in his head.” (It turned out that this was not true. There was no plate. But Draper had told his wife that story, and she believed him.)

“Did he get the injury in the war?”

“Well, he said he got it in North Africa, but he never said in so many words that he got hurt in combat,” she replied.

“What did he say about his injury?”

“He didn’t really talk about it, but he gets headaches a lot, and that was when he would complain about it. It seemed to get even worse when he was drinking a lot.”

On July 20, following private funeral services at the John C. Morgan Funeral Home on Hudson Avenue, a Requiem Mass was celebrated in St. Joseph’s Church on Franklin Street, after which Jennie O’Keefe’s body was transported to Holy Sepulchre Cemetery on Lake Avenue for burial.

On August 2, Draper was arraigned before Peace Justice Arthur Rickman of Greece. During the hearing, the justice read a letter written by a psychiatrist, Dr. William Libertson of Goodman Street North, who’d examined Draper for an hour and a half in jail and concluded that he suffered from dementia praecox, paranoid type. Draper had been hallucinating and having delusions for more than a year, so it was reasonable to assume that he was mentally ill at the time of the murder as well, Dr. Libertson said. Draper, he added, didn’t understand why he was in jail and was incapable of helping his own defense at trial.

After the hearing, Draper was transferred from the Monroe County Jail to the Rochester State Hospital for mental examinations. The psychiatrists who examined Draper reported that he was good to go for his murder trial. He was returned to the Monroe County Jail.

His trial was presided over by Judge James P. O’Connor, and caused quite the sensation, with the star witness being Mabel Draper, who testified that her marriage was no picnic.

“He’d accuse me of having affairs that he made up,” Mabel testified.

“Has he ever threatened you with physical harm?” Mr. Lacey for the defense asked.

“Yes. He threatened me with a revolver.”

“How long ago was that?”

“Not quite a year.”

“Were there other times?”

“Yes, on another occasion he said he was going to use a shotgun on me, but I managed to talk him out of it.”

The trial boiled down to a battle of the psychiatrists. The prosecution said Draper knew right from wrong. The defense said that was not always true. The lawyers gave the jury refreshingly brief closing statements.

Draper’s defense attorney sounded defeated as he said, “The People have offered proof to the effect that the defendant was very intimately connected with this homicide, there is no question about it. They have proved that. And they have proved that he was the killer, although no man living today knows what happened at the scene of that homicide.”

Judge James P. O’Connor charged the jury, a process that took a little over at hour, and sent the panel to the jury room to do their work.

On Thursday, April 24, after a nano-second of deliberation, Draper was pronounced guilty.

“Do you recommend that his life be spared?” Judge O’Mara asked.

“We do not,” the jury foreman said firmly.

The judge sentenced Draper to death in the electric chair.

The convicted man was ordered to be taken immediately to the Death House at Sing Sing, where Draper had a date to sit in the lap of Ol’ Sparky. A heavily shackled Draper, with two deputies as escorts, took a train to Ossining, N.Y. When he arrived, he was given the Number 13.

Before he could be electrocuted, there were more appeals to get through. But eventually, the day came. For his last meal, Draper wanted ice cream.

On July 23, 1953, the now thirty-three-year-old Draper walked silently to the electric chair and took a seat. As he’d taken up Catholicism while in jail, he was accompanied by Father Thomas Donovan. He was strapped into the chair at 11:01 p.m. and was pronounced dead three minutes later.

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2025 issue of (585).

Views: 0