On October 6, 2023, I was added to a group chat on Facebook messenger with eighteen people titled “ECLIPSE PLANNING.” Given my proclivity for niche gossip I was not immediately alarmed. But as my phone began to blow up with exact latitude and longitude coordinates and links to the best glasses for staring directly into the sun, I knew I had fallen into unfamiliar waters. I quickly googled “big eclipse soon” to verify that I didn’t miss something and that the group was planning their viewing of the solar eclipse more than six months away, on April 8, 2024. Everyone chattered with excitement about this once-in-a-lifetime event and nostalgic eclipse-adjacent memories. I tried desperately to grasp something in my own zeitgeist to compare this anticipation to. Perhaps the insatiable thirst I felt waiting for each episode in the three-part Vanderpump Rules Reunion to drop after Scandoval broke?

I am common-law married into a family who are prepared to produce their version of an episode of Bill Nye the Science Guy at any moment. My mother-in-law’s favorite thing in the world is to crack rocks with hammers and find special things inside. One might think a special thing found in a rock is a crystal or a gem, but the frivolity of such things pales in comparison to finding a fossil. When the family goes on vacation you can look around and see them all doing their preferred STEM activities: Diane, my partner’s mom, is fossil hunting, his oldest brother, Ben, is looking at birds, middle brother, Jake, is encasing bugs in resin, and my partner, Sam, is finding perfectly shaped skipping stones and telling me the aerodynamic nuances between the different rocks. I am looking off into the middle distance, yearning for a trip to Target.

I wouldn’t call myself vastly vapid and averse to science. The last “traditional” science I practiced was 1 grade Regent’s chemistry which I passed based on my networking skills and charisma alone and zero knowledge of any kind of noble gas. The space in my head where any kind of practical scientific knowledge should be stored is filled with unnecessary pop culture fun facts I am prepared to rattle off at any time. Did you know that J.R.R. Tolkien was kidnapped as a baby and returned the next day? Did you know that Baja Blast’s exclusivity arrangement with Taco Bell came from a threat to switch from Pepsi to Coke products and essentially came down to “Give us the exclusive rights to the best soda you will ever make because kids these days are only interested in Coca-Cola fountain drinks?”

Sam’s oldest brother, Ben Brown-Steiner, grew up in this household of nerds to be an atmospheric scientist and chemist. If you were to ask me what he does I would usually just say “cloud science.” He is just as wild as the rest of his family about this eclipse, but is best able to explain it to me like a toddler, which I appreciated for this assignment. Currently the eclipse has taken over his professional life, as he is swamped with proposals for scientific study of the event. “The eclipse actually changes the atmosphere,” he says. “I’ve got a bunch of colleagues who study the sun, and they’re having a field day with it.”

As someone viscerally aware of the incoming Special Once in a Lifetime Eclipse™ but not entirely sure why I should be excited about it, I had Ben give me the lowdown on why exactly this is such a marvel.

“There are multiple types of eclipses. There’s a lunar eclipse and a solar eclipse. By far lunar eclipses are more common, which is when the earth is casting a shadow on the moon, so the sun is on one side of the Earth and the moon turns a little red. That happens a lot.”

“So, like, in a lunar eclipse sandwich, the earth would be the ham?” I ask for clarification.

“Yes, Mary. The earth would be the ham. This one’s a solar eclipse, where it is a sun/moon/Earth [sandwich]. The moon is in the middle of the sandwich.”

“-The ham. The moon is the ham of the sandwich.” I interrupt, clearly adding value to this conversation.

He tells me more about the rarity of solar eclipses, especially total solar eclipses.

“They do happen a bunch, but they happen in a very small area. If you would like to travel around the globe, you can catch them on occasion. But in any particular spot they happen every twenty years, sixty years . . . ” The last total solar eclipse visible from Rochester was in 1925, and if you miss this upcoming one you will need to wait until 2044 to see one again in this area.

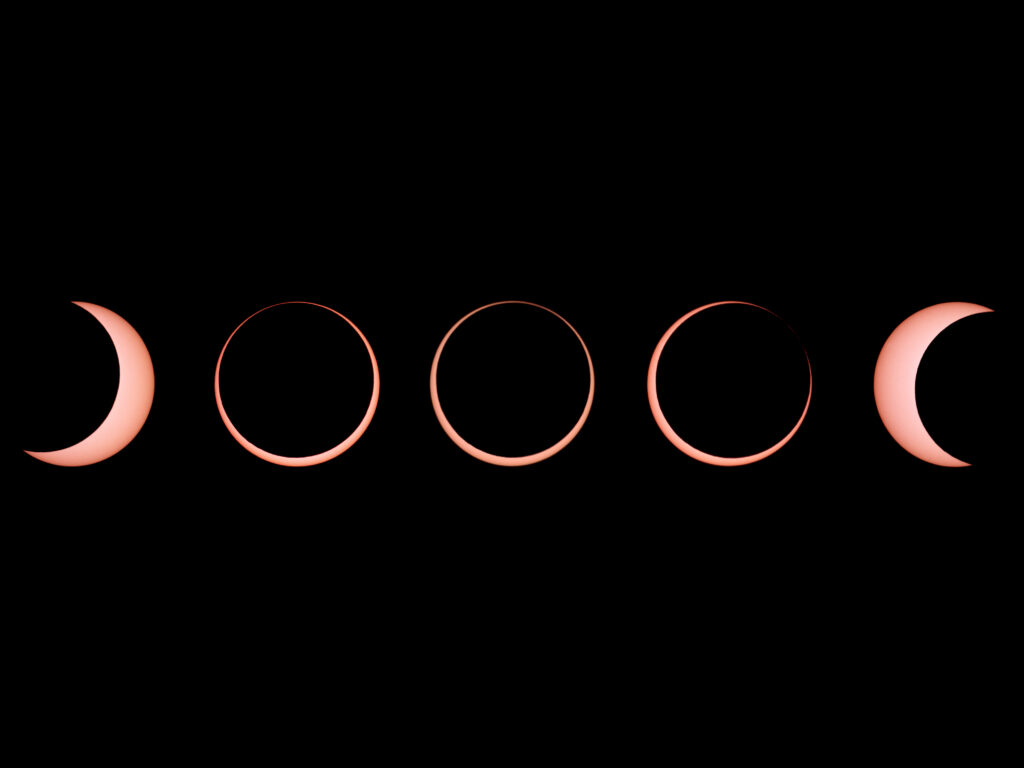

“The total eclipse is three to four minutes at the most; this one starts at 3:20 p.m. here in Rochester. That’s when the moon is exactly in front of the sun, and you get that ring effect. I think the whole thing is about half an hour long, including gradual dimming, true darkness, and then a gradual lightning.”

I ask him if he were to recommend the best way that one should experience the eclipse, if one is not in our freaky family that has planned out a five-hour road trip for this astral event, complete with eclipse-based accessories.

“I mean, the first thing is don’t look at it.” Even I know that one! You can find solar glasses fit for viewing the eclipse directly online in varying costs and qualities, including family packs if you chose to attend a viewing party like I am.

“There are other ways you can enjoy it, also,” Ben goes on. “You can reflect the image of the eclipse onto a wall with a small mirror. You can also see the eclipse indirectly through pinhole projection. You will be able to see the shape of the obscured sun in the way the light passes through leaves on trees or a hole that will cast a shadow. Instead of a pinprick of light, you will see the shape of the sun as it is covered by the moon.”

I ask how a climate scientist wants to experience the event. Is he going to stare up straight into the sky for thirty minutes? Does he need a neck pillow?

“I need to make sure I’ll be in as much of a cloud-free zone as possible; my plan is to do some heavy forecasting where the least cloudy zone is going to be. I’m going to watch it happen, take a look with the glasses when it hits totality, because you might be able to see some of the corona, and some of the little—”

“I’m going to need a definition of the ‘corona,’” I interrupt.

“The sun is a surface that’s like a roiling magnet. It’s a solar kind of flare that’s wrapped up in this magnetic sphere. So [during the eclipse] you could see these eruptions on the side, but you can’t see them regularly. The closest way to describe it would be that you’re gonna see spikes sticking out.”

“Okay. Okay. Like, like the Teletubbies Baby Sun. Sort of like a cartoon sun.” I assert, trying to parse out what “roiling” looks like exactly.

“Not quite as uniform,” The climate scientist tells his sister-in-law, who just compared a once-in-a-lifetime cosmic event to the Teletubbies Baby Sun.

“The big moment is the Ring of Fire. When the moon is directly in the center, and you see the ring around the entire sun. When the moon moves enough that the Ring of Fire disappears, sometimes you get a diamond ring effect. Where the moon moves away, and on the far side there is a little beam of light. You get a diamond-ring-type structure.”

For a family that is averse to melding spirituality into their science, Ben gives me a glimmer of magic toward the end of our talk. I ask him why a person like me who isn’t particularly inspired to go out of my way to watch the eclipse should make an effort to do just that. I have thought a lot about how a different version of myself who wasn’t lucky enough to be tangled up in this family would be hard pressed to leave the comfort of my home to see some dots in the sky. Sometimes you need to have a professional science guy get a little existential to finally grasp the power of it.

“The reason we can see the eclipse at all is because the moon is exactly the right size to block out almost all the sun without blocking it out entirely, making the ring of fire visible. If the moon was a bit closer it would block out the entire sun, and if it was a bit farther it would be too bright to see. The moon is like 200,000 miles away and the sun is 93 million miles away, but the area that we see from earth is more or less exactly the same. And that has not always been the case. And it will not always be the case, because the moon is moving around. You can consider it coincidence, or, if you’re a conspiracy type, maybe you’ll believe in divine intervention, but we are incredibly lucky to see such a thing at all. Most of us never will again.”