When Neil Armstrong stepped onto the lunar surface on July twentieth, nineteen sixty-nine, the world held its breath. The images that accompanied that historic moment—Armstrong’s first step, Buzz Aldrin’s stance beside the American flag, Earth rising over then Moon’s horizon—were seared into collective memory. But few realize that the film and cameras that captured these moments were crafted in Rochester, New York.

Robert Shanebrook, who went on to spend thirty-five years at Kodak in roles ranging from industrial photographer and researcher to product-line manager for Kodak Professional Films worldwide, recalls a particularly pivotal assignment early in his career. When he was just twenty-one years old, fresh out of school in March, Shanebrook had already completed two summers working at Kodak while attending RIT. With enough credits to graduate early, he called Kodak and asked to start in March instead of June.

“When I come along, I am a kid,” Shanebrook says. “I don’t think a lightbulb goes off. Everything is new to me. At that point in time, I don’t have a security clearance. This space thing is certainly important, but I am in awe of everything. I have a blank check to work as many hours as I want. If it is a rainy day, I can work. I have other things I am doing, but if it is for the camera, I do that first. I make sure it is my top priority. If we need something done, if we have a request, it gets done.”

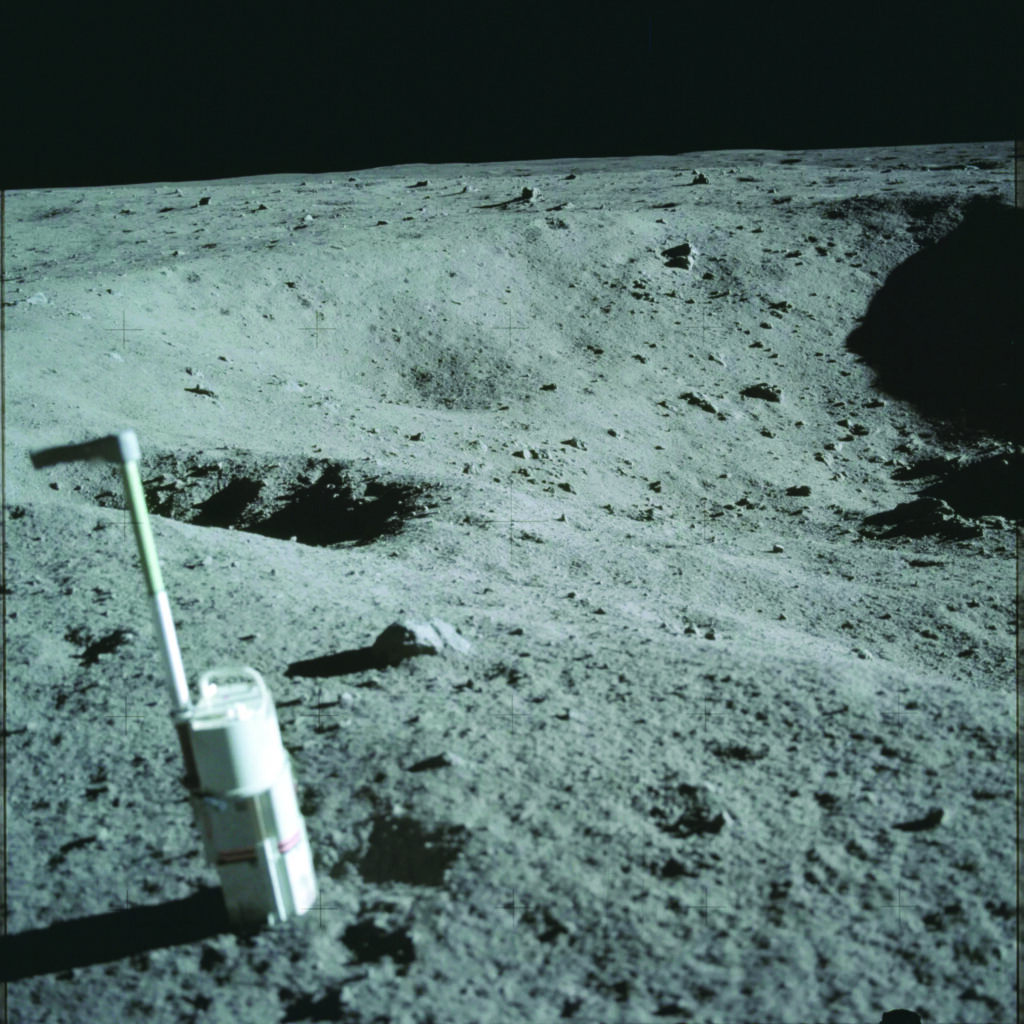

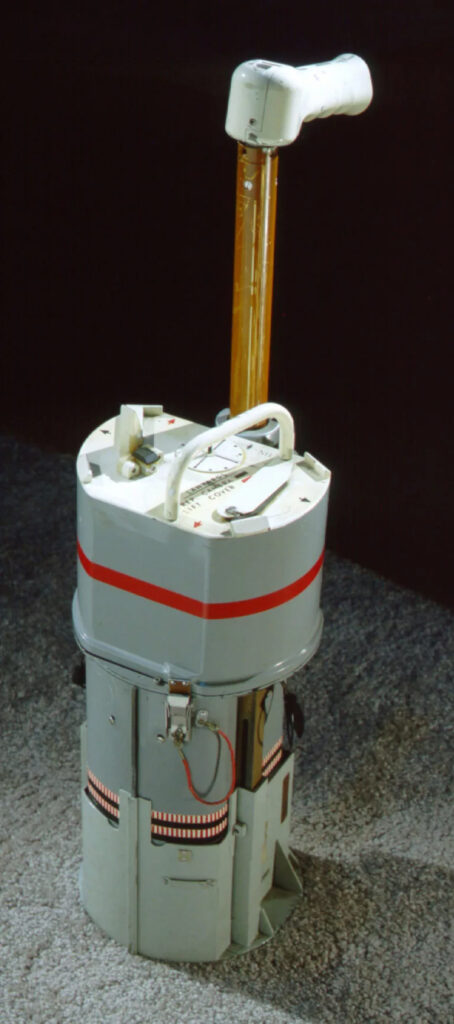

Shanebrook’s first job out of college involved helping to build the Apollo Lunar Surface Close-up Camera (ALSCC), designed to photograph the Moon’s surface in microscopic detail. Armstrong and Aldrin brought lunar soil samples back to Earth, but NASA also wanted to understand the Moon’s surface structure before it was disturbed. Shanebrook’s work, as one of the youngest members of the team, placed him at the heart of a historic mission.

“The Apollo Lunar Surface Close-up Camera has a very specific and unusual purpose,” Shanebrook explains. I ask him, if he closes his eyes and thinks back, what part of that camera’s design or testing makes him most proud—and why? “It works. There is always that moment of uncertainty if it will work or not—it works!”

The camera was a marvel of precise engineering. “The design is robust. It uses microfilm lenses, very high quality. The space it has to fit in is circular and just twelve inches tall. There is an ergonomic diagram to guide its design. And it has to be built for lunar gravity. Weight is important. Every fraction of an ounce counts.”

The contract to build the ALSCC was completed on an astonishingly short timeline, which shaped both the atmosphere in the lab and Shanebrook’s approach to work. “We colocate everyone working on it in a brick building called the Candy Factory near Hawkeye,” he says. “Everyone there is assigned to the same project. If there is something to be done, they do it. We are centrally focused. No distractions. No one is let into the building if they aren’t on the project.

We want this to be successful. There is a timeline for everything because of NASA’s requirements. A lot of things are not known. We have an Apollo 11 glove to experiment with—this big clumsy glove—and we have to test everything to make sure the camera works. The astronauts are not in favor of the camera; it is just another thing they have to learn.”

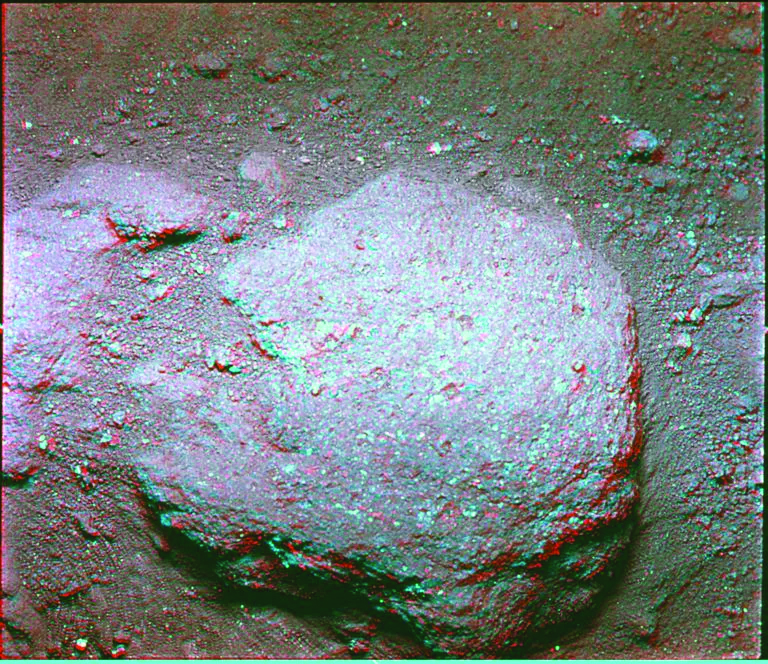

Fifty-plus years later, Shanebrook reflects on the images he helped create with a deep sense of pride. “We learn so much in those first years. Those images turn out to be very revealing. No one is sure what the lunar surface is like. Some people think the gray dust could be as much as twelve inches deep. We discover it is only one or two inches thick. The significance affects everyone. I know what I am doing is special. I make sure I touch every camera—I want to make sure the camera they use (there are at least two dozen made) is one I have touched. Even though I am a kid, I know this is more than making Instamatic cameras. When it actually happens, my wife and I get up and watch the moonwalk on our black-and-white TV. I probably still have that TV today.”

Shanebrook is also reflective about legacy. “The moon camera is special, but my contributions are minor. I am most proud of any contributions I have made to photographic films. I am personally most proud of being associated with people who make film. We stand on the shoulders of giants, and the technology improves tremendously. That work is done generation after generation at Kodak. The same materials that Eastman used are basically the same, but over time we all contribute to the advancement of film as an art, a science, and a craft. Today we have the greatest film ever produced.”

Later in his career Shanebrook authored Making Kodak Film, a definitive technical manual detailing how the company creates its photographic products. But in those early months, he focused on making sure the ALSCC functions flawlessly in the harshest conditions imaginable.

Behind the glossy images broadcast across televisions worldwide were Rochester labs where chemists fine-tuned emulsion layers, engineers tested film reels under simulated space conditions, and young professionals like Shanebrook ensured that history was recorded with precision. Kodak engineers developed a custom version of Ektachrome film, engineered to withstand extreme radiation, temperature swings, and zero gravity. Every frame that travels millions of miles from the lunar surface back to Earth carried Rochester’s signature.

The George Eastman Museum, custodian of Rochester’s photographic legacy, continues to preserve these artifacts, a reminder that the city’s contributions leave an indelible mark on humanity. In a film-themed issue celebrating Rochester’s cinematic and photographic impact, this story is a testament not only to the Moon landing but to the ingenuity, the craft, and the vision that make it possible. From Rochester labs to the lunar surface, Kodak captures history, and in doing so, ensures that a piece of our city forever orbits the imagination of the world.

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2025 issue of (585).

Views: 16