I am seated in the balcony of the Dryden Theatre at the George Eastman Museum. The room is full of film aficionados of all ages, and the projectionists take their places in the booth at the back. The audience sits in collective anticipation as the folds of the stage curtain in front of us starts to rise like liquid gold flowing upward. A large white screen is slowly revealed as the curtain rises. The lights go down, and we are instantly transported back in time as the picture starts and the sounds of the past fill the room.

The first Nitrate Picture Show was held in 2015 at the Dryden Theatre, one of only a handful of spaces in the world certified to project the highly flammable nitrate film. This four-day festival, devoted to screening original nitrate film prints from archives around the world, is held each spring in Rochester.

What makes the Nitrate Picture Show particularly unique is that 500 people have purchased tickets for ten feature films and ten short films even though they have no idea what they’re about to see. As per tradition, only the first film is announced ahead of time. The remaining titles are revealed on the first day of the festival. To keep the mystery going, the last film is nicknamed A Blind Date with Nitrate, and the title is not known until the curtain rises and the light from the projector hits the screen for the final show.

Past festivals have included original release prints of Walt Disney’s Pinocchio, Casablanca, Meet Me in St. Louis, A Star is Born, and The Wizard of Oz. “The Nitrate Picture Show is our Oscars, our Grammys, our World Series,” says Courtney Holschuh, archives technician at the Library of Congress. People gather from around the world to experience films as original audiences did.

Over the next few days, we laughed at ridiculous commercials and French comedies from the 1930s, we rooted for Henry Fonda in You Only Live Once, and we watched in wonder at the colors in Spook Sport and Colorful Flight. A wave of nostalgia washed over the crowd during Rhapsody Rabbit featuring Bugs Bunny and Trois Petits Cochons (a French dubbing of The Three Little Pigs). Watching old travelogues, one couldn’t help but think of all the people for whom these reels were a nine-minute vacation.

Film selection is a complex process as the showing may cause degradation or even be the last time an audience is able to view the film in its original form. Even with this risk, the curators of these films believe wholeheartedly that they are meant to be viewed by a large audience, not kept in the dark forever.

In the late 1800s it was common to own products made of nitrocellulose, such as men’s collars, women’s skirts, billiard balls, and even the heels of women’s shoes. You can imagine the dangers of stepping on a cigarette with a nitrate heel or standing too close to the fireplace in a full skirt. Nitrate film was replaced in 1951 when Kodak came up with triacetate film stock, which had the same look and appearance without the flammability.

This festival is not just a celebration of the nitrate medium but also of the people who devote their life’s work to preserving these films. I had the privilege of visiting the Louis B. Mayer Conservation Center to take a rare behind-the-scenes tour of the nitrate vaults with the people who work devotedly on protecting these pieces of history.

At an unmarked location thirty minutes away from the George Eastman Museum, more than 24,000 reels of nitrate film are meticulously preserved. Deb Stoiber, collection manager for the moving image department, has been working at the George Eastman Museum and teaching in the L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation since 1988.

“I grew up in Fresno, California, and I was a projectionist through college. I wanted to know what happens to the films after they leave the theater.” She enrolled at the Selznik School, planning on moving back to Los Angeles after a year, but stayed after falling in love with Rochester’s four seasons and her now husband of twenty-five years.

For Kirk McDowell, associate collection manager, it is a longtime dream come true. “I think as a kid, I must have seen an old movie and said, ‘this was restored at some point.’” He attended a school with a major university film archive before attending the Selznik School and went on to work at the Library of Congress before joining the museum in 2021.

In addition to restoring and preserving the films in the vault, Stoiber and McDowell manage all the loans to and from other archives. They care for many significant pieces of film history, including the private collections of Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee.

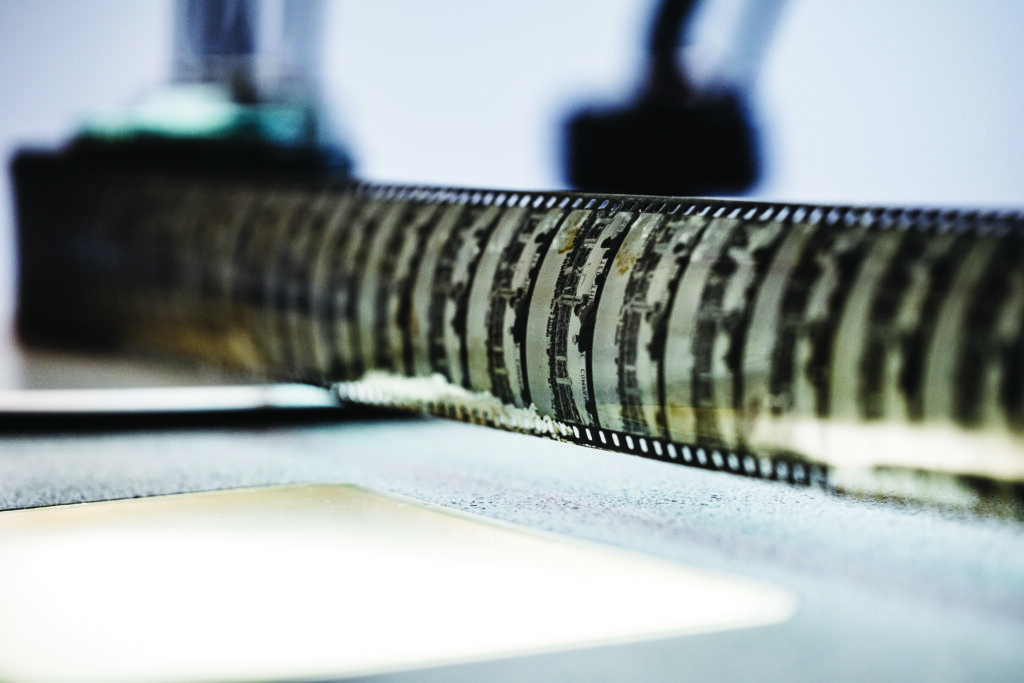

We start the tour in the inspection room, where Stoiber’s small team works on the films. There is a staging system with lots of doors and small rooms to keep any mold or bugs from making their way to the film collection. We look at an original 1939 dye transfer print of Gone With the Wind. Filmed in Technicolor, we can see the quality of the color that audiences would have seen as opposed to the digital versions we have today.

McDowell shows us the variable density track, a sequence of black and white bars on the side of the frame reproducing the sound. “Imagine Clark Gable’s voice,” he says. “Here you can actually see it.” We take a look at President McKinley’s inauguration parade from 1897, one of the earliest films in the collection.

These visually captivating pieces of our history can also be volatile. Nitrocellulose is an unstable but organic substance that will decay, especially if stored in poor conditions. If left alone, the images will fade, followed by the presence of a sticky texture and bubbling effect. The film will eventually solidify and finally disintegrate into a pile of dust.

Stoiber likes to wind through each film every few years to prevent decay, an activity she calls film yoga. “I always say, the film is like a baby. The first year will determine the rest of its life. All of the Technicolor films are in beautiful shape because Technicolor made a quality product. They stored it properly. Those are the Judy Garland movies. Those are the Clark Gable movies.”

We put on our sweaters and coats to enter the vaults, which are kept at a precise temperature and humidity. On the entire East Coast, there are only two other facilities equipped to house nitrate film like this, the offsite vault locations for the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. Each of the twelve vaults holds more than 2,000 films. Stoiber intentionally stores prints and negatives separately. She explains, “If I lose this vault to fire, flood, earthquake, o riot, I don’t lose all my elements on that title.”

We gather around to look at an original negative of The Wizard of Oz, and Stoiber laughs, “This is the most preserved movie in the intergalactic universe.” This reel filmed in Technicolor begins with Dorothy opening the door to Munchkinland and was in the film camera on set with Judy Garland and Victor Fleming on the day of filming back in 1938.

We explore the vast selection of titles from Hollywood classics to newsreels, even propaganda films confiscated from 1945 Berlin. “We have Gone with the Wind, and we also have footage of the Armenian genocide in 1920,” Stoiber says. “We keep it; it is a living memory of our history and of our past as a human race. Our job is to keep history alive so that hopefully people can learn from our mistakes, be entertained by Hollywood movies, learn from newsreel footage, get interested in history, and overall become better people.”

Next year’s festival will be held June 4–7, 2026, and tickets will be on sale December 8. Your pass includes screenings of all of the films as well as live music performances, a swag bag, and access to the entire museum and galleries, including tours of the world’s most elaborate cinematographic technology.

To help the George Eastman Museum preserve and share important cinematic and photographic heritage, you can donate here: eastman.org/individual-giving.

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2025 issue of (585).

Views: 99