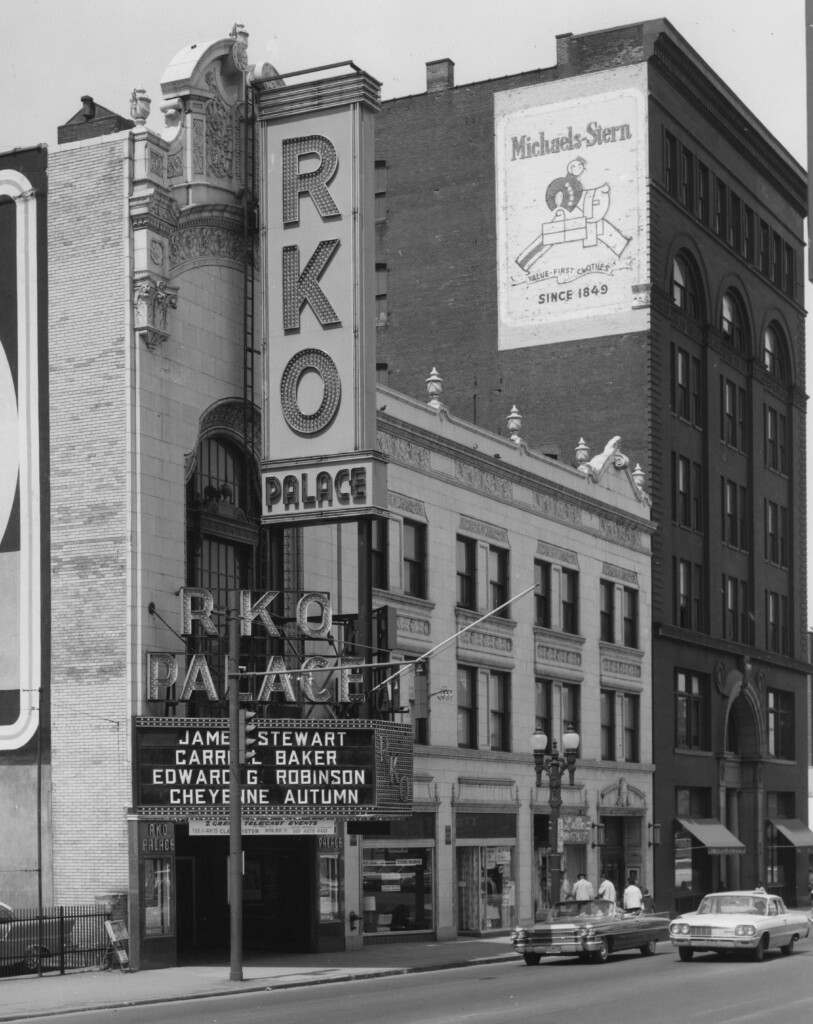

During a holiday vacation when I was eight (1964), my mom took me to see the movie Bye Bye Birdie in downtown Rochester. Our theater that afternoon had been built during the roaring twenties, when nothing seemed extravagant. I remember my feeling as I entered. My mouth dropped open. I stopped blinking. It was some sort of movie heaven. Today, I realize I was looking at a masterwork of architecture and décor, a multilayered structure of Jazz Age excess. This theater was to neighborhood movie houses what Gatsby was to Friday night get-togethers. As a boy though, I merely gaped at the vastness of the biggest room I’d ever been in, seemingly twice the size of any cathedral I’d entered. Someone, I sensed, had spent a lot of money and energy making sure I was in awe even before the lights went down and the movie began. Going to the movies in downtown Rochester back in the day was an experience unlike any we can have today. Downtown cinemas such as the Loew’s Rochester, the Paramount, and the RKO Palace (where my mom and I were) not only presented motion pictures on huge screens 100 feet wide but also offered patrons a luxurious experience, like visiting Versailles in France or the Royal Albert Hall in London.

For a few hours anyway, patrons lived in an environment of limitless prosperity otherwise known only to royalty and the world’s richest people. In addition to the ambiance, those huge silver screens were lit over the years by Hollywood’s greatest art, like Gone With the Wind, Ben-Hur, The Wizard of Oz, and West Side Story. And it cost only pocket change to get in.

The largest of the downtown palaces was the Loew’s Rochester, known in town as “the Loew’s,”at 130 South Clinton Avenue. It opened on November 7, 1927, as part of the Schine’s Theater Chain but was soon thereafter purchased by Loew’s, Inc. Construction costs were said to be $3 million, $400,000 of that in beautiful Italian marble for the walls.

The floors were covered with rich oriental rugs. From the ceiling hung five seven-foot chandeliers. The décor featured bronze light fixtures, murals, and leather-upholstered chairs. With a seating capacity of 3,581 seats, it was the largest theater between New York City and Chicago.

On opening night, a three-hour show was presented: a live Ukrainian ballet followed by the Ronald Colman picture The Magic Flame. A newsreel onscreen and standard vaudeville acts on the stage filled out the program.

Between acts the theater organist, with the dubious name C. Sharpe Minor, played popular songs of the day on a huge Marr & Colton pipe organ, one of the largest ever built, with hundreds of pipes, miles of wires, and thousands of electrical switches, controls, and stops. The organ took six months to build.

In 1964, with TV’s ubiquity shrinking the cinema’s power, the Loew’s was used for live closed-circuit television showings of top sporting events like the NFL championship game (precursor to the Super Bowl) and the heavyweight championship boxing match between Sonny Liston and Muhammad Ali, then known as Cassius Clay.

That spring, the letters on the theater’s marquee were changed to read: “THE WALLS CAME TUMBLING DOWN featuring the Atlas Wrecking Co.” Room was needed for Xerox Tower. The demolition team hoped to salvage large pieces of Italian marble but found too many cracks due to the building settling. Loew’s never lost out on business however, building two new suburban neighborhood cinemas in the next year, one in the Pittsford Plaza and the other, the Towne Theater, across Jefferson Road from South Town Plaza—both devoid of luxury.

The Piccadilly Theatre opened on November 25, 1916, at 33 North Clinton Avenue. Made of steel, brick, and concrete, the Piccadilly was the first of Rochester’s luxury theaters to be built specifically for motion pictures. It got off to a rocky start, however.

Even before it opened, the owner of the competing Regent Theater started a campaign to slander the Piccadilly, including accusing the structure of code violations. They didn’t exist, so the Piccadilly took out a newspaper ad claiming to be the handsomest and safest theater in town.

The Palace offered patrons a luxurious experience, like visiting Versailles in France or the Royal Albert Hall in London.

The issue was settled the next week when the fire marshal said the theater would never have opened had it not been safe.

The initial program included the Piccadilly Orchestra playing soundtracks for the flicker (Miss George Washington starring Marguerite Clark) and a travelogue by globe trotter Burton Holmes. The theater was the real star. Patrons gaped at the velvet-carpeted rotunda, the rich red curtain, the potted palms that lived in the orchestra pit, the Venetian fountain. As its name would imply, there was a foggy London theme, with earth tones dominating; seats were gray wood upholstered in pink.

The Piccadilly underwent a pair of name changes over the years—becoming the Century in 1931, and the Paramount in 1948. The theater survived into the 1970s and endured the indignity of being vivisected into a multiplex before it was razed in 1974.

Across the street from the Paramount was the theater most beloved by Rochesterians, the sumptuous Palace Theater, which opened on December 25, 1928, at the corner of North Clinton Avenue and Mortimer Street. The Palace—originally part of the Keith-Albee chain and later owned by RKO—didn’t have quite the capacity of the Loew’s, but it was close with 2,916 seats. What it had was glitz: four enormous crystal chandeliers hanging from its domed ceiling—“a thousand lights,” (ads boasted), a grand foyer with mirrored walls that seemed to go on forever, a $75,000 Wurlitzer organ on an elevator platform, and a crimson curtain. For live acts, the stage measured 100 feet across and thirty feet deep. Between the front lobby and the auditorium was the “transverse lobby” or inner lobby, a bizarrely large space that served no reasonable purpose until the 1950s, when TV competition forced theaters to sell concessions. At the Palace, you could feel like a Vanderbilt even when you were waiting in line for popcorn. (The organ was considered such a draw that the organist’s last rehearsal before the Christmas Day opening was broadcasted by WHAM radio.)

Special attention was given to the lounges. The ladies’ was hung with heavy gold draperies, blue-and-gold satin walls, gilt chairs upholstered in needlepoint, a fireplace with a coal grate, and a piano for women who liked to listen to tickled ivories while doing their business. The men’s room had no piano but was paneled in walnut with overstuffed leather furniture, ornate “smoking stands” (ashtrays), and a great fireplace of carved Italian marble.

The Palace opened at the very end of the silent film era and was already equipped for sound movies. When Snow White and the Seven Dwarves opened in 1937, our parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents went to the Palace to see it.

Bob Hope, Martha Raye, Eddie Cantor, and the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra performed at the Palace—and it was said that the dressing rooms backstage were every bit as opulent as the rest.

During World War II, concerned citizens came to the Palace to hear radio broadcasts of war news over the state-of-the-art sound system. During the late 1940s, the Palace became one of the first theaters to have midnight shows, usually a double feature of horror classics.

Ten years later, when Hollywood first felt the bite of TV, the movies fought back with new technology, such as CinemaScope, a Bausch & Lomb widescreen process that was perfected and then debuted in the movie The Robe at the Palace. But the efforts to combat television were in vain. TV was too convenient, and even when Rochesterians did go out to the movies, they were more apt to go to one of the suburban and neighborhood cinemas that were popping up.

[gtx_gallery]

The first picture to be shown at the Palace on Christmas 1928 was Scarlet Seas, starring Richard Barthelmess. The last, on July 28, 1965, was Von Ryan’s Express starring Frank Sinatra. The Palace was demolished that September, taking a piece of Rochester’s heart with it. Among the items salvaged was the Wurlitzer organ, which now lives at the Auditorium Theatre on Main Street.

To best imagine what it was like to go to the Paramount, the Loew’s, or the Palace, I recommend a visit to the Eastman Theatre, which opened on September 4, 1922. It is luxurious and spacious like the others— with original seating capacity of 3,352, cut down to 2,260 during a 2004 renovation—but unlike the others, it still stands in all of its glory. Though the Eastman hasn’t been a movie house since the silent days of Buster Keaton and Mary Pickford, it has for generations been Rochester’s preeminent performance space. Go see the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra.

As for me and the other seniors who recall the downtown movies, we are blessed to cherish those memories in the ornate palace of our long ago.

Views: 195